Hosted by The Young Activist Network for Abortion Advocacy (YANAA) in collaboration with the Asian-Pacific Resource and Research Centre for Women (ARROW) and the YP Foundation (TYPF)

28 and 29 August, 2023

Report by Arundhati Nath, Independent Consultant

Summary

The Young Activist Network for Abortion Advocacy (YANAA), in collaboration with the Asian-Pacific Resource and Research Centre for Women (ARROW) and the YP Foundation (TYPF), organised an Asia Regional Meeting spanning two days, inviting young activists from the region, with the objective of sharing and cross-learning about the national social and legal contexts, the needs of young abortion rights activists and discussing strategies used in advocacy. It also had a forward-looking aim of strategizing towards developing an Asia regional chapter of YANAA Global.

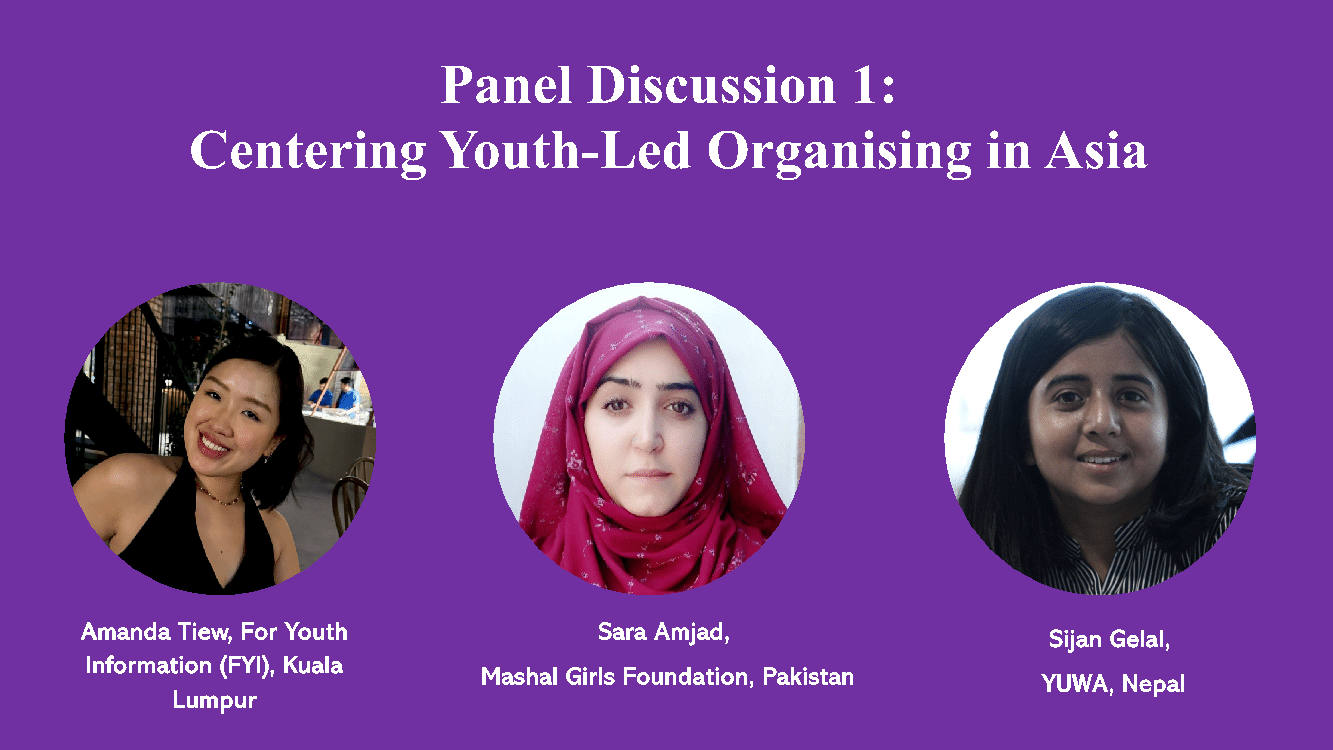

On the first day of the meeting, two panel discussions were organised. The first panel discussion was titled, ‘Centering youth-led organisations’. The moderator for the session was Shruti Arora, Co-ordinator, YANAA. The speakers in the session were as follows:

In this panel discussion, the speakers shared the values and principles that they uphold as a youth-led organisation working on SRHR and abortion, and put forth their needs. The speakers listed decision-making by girls and young women, respect, transparency, empathy, inclusivity as some of their main values and principles, and spoke of the opportunities of continuous learning and unlearning as one of the best aspects of being part of a youth-led organisation. Since working with colleagues of the same age means most of them are going through similar issues, that makes the culture of youth-led organisations more friendly and relatable for colleagues. Young people’s identities are not homogenous, so while there might be similarities, there are also differences in their experiences. Marginalised young people should be provided with equal opportunities to participate in youth-led spaces. The need for funding and resources for SRHR and abortion advocacy was unanimously emphasized. The speakers also pointed out the need for comprehensive information about safe abortion methods and how to access such services, and the need for engaging more young people who can take the information back to their communities. The need for accountability was brought up – to question the various stakeholders if they have truly incorporated the voices of the youth, without tokenizing them, and if those voices have been embedded where they could make a difference. The need to ensure that young people not only have a separate space but are also not siloed within the mainstream agenda was also pointed out.

The second session was titled, ‘Deep dive into national laws, access and opposition’. The moderator for the session was Indah Yasuri, Programme Officer, ARROW. The speakers in the session were as follows:

The speakers focused on expansive knowledge-sharing on legal and policy dimensions in regard to safe abortion in their respective countries, and the challenges of access and opposition that they encounter. Our speakers and participants extensively discussed the laws related to abortion in their respective country. While the legal system looks more progressive in some countries like Vietnam and Nepal than in the others, the discussion brought into light the common problems of access that unites countries of the region – social stigma, high pricing and affordability issues, provider bias according to the abortion seeker’s social location, binary language in legal texts, poor implementation of existing laws, not abiding by the WHO guidelines on safe abortion, etc. An interesting point that came up was how colonial laws are the background of the restrictive laws in the present. The penal code that was implemented in the Asian countries through colonial legal reforms which exist are very archaic and ancient in their framing and criminalise abortion in most of the countries. Opposition from religious and conservative groups and male-dominated policy making spaces have hindered advocacy especially in the Philippines and Sri Lanka. The need for cross-country solidarity in the movement was further exemplified by an enlightening discussion on the highly expensive abortion care in Japan and the resultant problems faced by migrant Vietnamese workers. In spite of existing within restrictive spaces, the youth-led organisations that our speakers represent continue to advocate for safe abortion in various ways – through abortion stigma elimination workshops, capacity building by partnering with the grassroot community, tailoring advocacy messages to align with cultural norms and values, recording and documenting stories and data, and so on.

(Sarryna’s PowerPoint presentation can be accessed here).

(Kazuko’s PowerPoint presentation can be accessed here).

(Laxmi’s PowerPoint presentation can be accessed here).

(Priskila’s PowerPoint presentation can be accessed here).

On the second day of the meeting, smaller group discussions were organised. Since YANAA is the only youth-led, global abortion network, an Asia regional chapter of YANAA will enable representing the region in international advocacy forums. Suggestions from the participants were made about enabling the members to work together to scope out funding opportunities – the network could come together to scope out funding available for abortion advocacy in Asia, and something like a South-South collaboration consortium could be leveraged to apply for certain grants together as a region. Intervening in policy ideation together, collectively scoping out spaces that we could extend our advocacy, sharing resources like toolkits, regional briefs or advocacy strategies, conducting regional research on abortion, and utilizing art to advance our advocacy are some of things that are expected from the network. Opposition mapping and creating counter-narratives, as well as working towards the decriminalisation of abortion were also emphasized. The importance of including artists, creatives or social media influencers who are loud about abortion rights with their particular demographic was also emphasized. A suggestion was also made to engage in spaces that talk about climate justice and livelihood, as well as queer spaces, in order to take an intersectional, cross-movement approach to talk about abortion rights in these spaces. Suggestions were made to create some specific outputs, like a report of this particular meeting, to approach potential donors for funds and explain to them the need for such a network.

Participants

- Crissar Mundin, Philippine Safe Abortion Advocacy Network (PINSAN), Philippines

- Yunishaa Loga, Reproductive Rights Advocacy Alliance Malaysia (RRAAM), Malaysia

- Sonali Silvaa, SheDecides, Sri Lanka

- Shilpa, Visible Impact, Nepal

- Ha Phan, Centre for Creative Initiatives in Health and Population (CCIHP), Vietnam

- Garima Srivastava, ARROW, India

- Cromwell Cruz, Young Advocates for SRHR (YAS), Philippines

- Kazane, Action for Safe Abortion, RHR Literacy Institute, Japan

- Sumanjari Pradhan, YUWA, Nepal

- Duong Ho, Centre for Creative Initiatives in Health and Population (CCIHP), Vietnam

- Archana Seker, Safe Abortion Network (unregistered), India

- Shilpa Lamichhane, Visible Impact, Nepal

- Aquilla Izzi, Youth Coalition for Sexual and Reproductive Rights (YCSRR), Indonesia

- Mark Devon Maitim, Young Advocates for SRHR (YAS), Philippines

- Pushpa Joshi, YoSHAN, Nepal

- Nurul, Samsara, Indonesia

- Amanda Tiew, FYI-KL

- Sara Amjad, Mashal Girls Foundation, Pakistan

- Sijan Gelal, YUWA, Nepal

- Kazuko Fukuda, #Nandenaino Project, Japan

- Priskila Arulpragasam, Youth Advocacy Network, Sri Lanka

- Sarryna Gesite, Women’s Global Network for Reproductive Rights, Philippines

- Laxmi Choudhary, YoShan, Nepal

- Vinitha Jayaprakasan, The YP Foundation, India

- Deepshikha, The YP Foundation, India

- Nayanshree, The YP Foundation

- Indah Yasuri, ARROW, Indonesia

TRANSCRIPT OF THE FULL DISCUSSION

WELCOME ADDRESS BY SHRUTI ARORA, COORIDINATOR, YANAA

Hello, good morning, good afternoon to everyone. I am Shruti, and on behalf of YANAA, The YP foundation and ARROW, I welcome you to the Youth for Abortion Asia Regional Meeting. Research on unsafe abortion suggests that of the 43.8 million induced abortions globally, 21.6 million are estimated to be unsafe. Nearly all (which is 98%) of unsafe abortions take place in developing countries. In the Asia region, age-segregated data shows that 34% of unsafe abortions are among women aged 15-24 years, and 59% are among women aged under the age of 30. More large-scale research is needed among the communities like transgender and gender-diverse people in Asia to learn the extent of unwanted pregnancy among them and their experiences seeking and having abortion. As the data shows, young women are the most affected by the abortion laws and the abortion stigma in Asia.

You might already be aware that the theme for this year’s International Safe Abortion Day, which is on the 28th of September, is ‘Unstoppable Movement’. The sub-theme of this year is ‘Young People’s Leadership’. Keeping with the spirit of the theme, we have planned and organized this meeting.

In the last decade, we have seen many young people voicing their opinions and demands for the right to safe abortion for everyone. Young people’s leadership is critical to making your movement unstoppable. Before we begin with the first panel discussion, I would like to give a shout out to the organizing and planning group of this meeting:

Wafa Adam, who is from Sudan and is a co-founder of the YANAA Network with me; she represents the Middle East and North Africa region within the YANAA Network.

Vinitha, Deepshikha, Prabhleen and Nayanshree of The YP Foundation.

Indah, who is a YANAA Steering Committee member and also works with ARROW, as well as Garima Srivastavs of ARROW.

Arundhati Nath, who is doing the documentation for us today.

Thank you, planning and organizing team, for finally having the meeting today!

Quickly, before we begin, here are some housekeeping announcements:

We want to make sure this is a safe and conducive space for all the participants. Please refrain from sharing anything inappropriate in audio, chats or written content. Participants, please do not take any photographs or video recordings of the workshop proceedings. To eliminate any noise, participants are requested to keep themselves muted during the presentations. Speakers must keep the videos on, and participants can keep their videos on. If you have a question, please use the ‘Raise your hand’ feature or write your question in the chat box. We do want to make this workshop very interactive, so we have kept time for discussion after each panel discussion today. Please note the workshop will be recorded for internal documentation, and we will publish the report of this meeting. In case anybody would like to remain anonymous, please get in touch with us as soon as possible.

We can move to the first panel discussion now. We have four speakers for the first panel discussion, which is titled ‘Centering Youth-led Organising in Asia’. I would welcome all the four speakers and request them to turn on their cameras please. We will be having this discussion in two rounds of responses from our speakers, and we will open the floor for discussions with participants for the last 30 minutes of the discussion. I would request the speakers to please maintain the time allotted.

DAY 1:

FIRST PANEL DISCUSSION – CENTERING YOUTH-LED ORGANISING IN ASIA

(Facilitated by Shruti Arora, Coordinator, YANAA)

In this section, the speakers answer the following questions: What are your values and principles, and some of your needs as a youth-led organisation working on SRHR and safe abortion? How do you think youth-led networking can be strengthened regionally? Do you have any recommendations on making advocacy spaces more youth-led and youth-inclusive?

Sijan: Thank you so much, Shruti. First of all, thank you so much for having me and having YUWA in the panel, and I’m really glad to see everyone here in the panel and the audience as well. So, for the first question: Basically, the panel is all about youth-led organizations and focused on youth-led principles. The organization that I belong to, like you have mentioned, is called YUWA, and here everyone works for young people, with young people, and all of us are from the age 18 to 29. So, it’s a completely youth-led organization that I now belong at. When I have to talk about what does it feel like to be a part of a youth-led organization where all the values and principles are youth-led, I would say, first of all it’s very fun to work with young people with a similar mindset. You have energy to try, you have a lot of energy to do new things. We do face with failures as well; as young people we do have a lot of fears while working in an organization as well, but then we always have that zeal – we’re not afraid of making mistakes, but then we also know where do we stand and what do we really envision for ourselves as an individual or as an organization.

When it comes to values and principles of a youth-led organization like you specifically mentioned, I think one of the major values or principles that outcasts youth-led organizations from other organizations is empathy that a youth-led organization carries. I think that’s one of the biggest values propositions a youth organization has while working in any field, either that be of SRHR or any or the field. We are an emotional being, especially when we are young, and we have a lot of empathy while working so we can actually feel what the other person – what our beneficiaries – might be feeling. So, I think empathy is one major factor that that makes us very loud and proud about what we are doing at this point of time.

Now directly coming to this specific topic about SRHR and abortion and working on it as a youth-led organization, I would say it’s a very big challenge, because you’re yourself young, you’re exploring yourself and you’re trying to make other people understand SRHR and also what safe abortion is. We go through a lot of challenges on a regular basis; like we go to advocate and we tell people, “Okay this is important, you need to do this”, but then people really do not believe you because you are young. They think that we’re just blabbering and it’s all about our fantasies and not facts that we’re talking about. So, there are a lot of challenges, a lot of ups and downs and roller coasters that we that we go through as a youth-led organization while we work especially in the field of SRHR, and especially when we belong to a country where SRHR very stereotyped. When we have started talking about SRHR in public and we started advocating about certain things, everybody would not question only us but also our parents, like what kind of upbringing did they give to their children. So, it’s like you have to balance out everything as well while you’re working in the development sector in a developing country like Nepal.

While we are talking about our needs as a youth-led organization, first thing is, we want people to believe in us. It might not sound very tangible but it’s one of the most important factors that we seek from any stakeholders that we work with. We want everyone to trust us – trust our instincts and trust what we want to do, because that’s where I think the entire process of bringing in change starts. We work with a lot of stakeholders but sometimes we feel, “Do they actually trust us? Or it is just because we are young people that they’re working with us? Are they just trying to tokenize us as young people?”

So, I think, one of the first needs is that we want people to believe us. The second thing is we definitely need a lot of resources. This is because as a youth-led organization we try to mobilize a lot of young people. While we might not be giving them salary because it’s not possible when you yourself are working at a youth-led organization, we definitely need resources because as a young person when you’re working, when you’re traveling for advocating about certain things, when we mobilize young people for that, one thing that really concerns us is that while we cannot pay them, we also don’t want them to bear their own expenses. So, funding and resources it’s always one of our major needs, something tangible that we as a youth organization require at this point of time. And when we talk about funding and resources it’s not only about monetary support, but a lot of times we need technical guidance. Because we might have the zeal and but then other person might have the required experience. So, if we could bring the experience of someone who has worked for years and years in this field together with the energy of young people like us, I think that would be the best outcome that we could deliver as a youth-led organization.

Summing up to everything that I have to say, being young people working in youth-led organization is one of the beautiful experiences that anyone could have; I think a lot of us here would actually agree to that, because we feel like a free bird at times, we feel exhausted at times, but then at the end we realize “okay, we are here for a cause and one day of hustle will actually make an impact on somebody’s life.” So, it actually feels good at times, and I myself am very grateful to be a part of a youth-led organization because I get to meet a lot of young people who have similar thoughts and even sometimes clashing thoughts such that we could actually have a good, healthy debate, like “okay I believe on this, and I think you should believe on this”. Every other day we learn and we unlearn.

Shruti: Thank you, Sijan. Sara, you can go next, and if you can also say what your values and principles are as a youth-led organization, as well as talk about the needs of your organization. Over to you, Sara.

Sara: Hello everyone! First of all, I would like to thank Shruti and YANAA for considering me as a speaker for today’s panel. If I talk about my place, I belong to Swat, Pakistan, and we are working on the borderline of Afghanistan with young people on SRHR and menstrual hygiene and safe abortion. The principles and values of our organization is that we focus on making the young people, the young girls, decision makers. So first of all, I will say that we are a youth-led organization – we are five to six members and all aged 18 to 28, so we are working with like-minded people. We work with different community members and stakeholders like schools, and also go to houses in the community to raise awareness about SRHR, menstrual hygiene, and safe abortion.

In our society, menstrual hygiene and SRHR – these are some things we cannot talk about in public; it’s a shameful thing. Especially abortion – it’s a very enormous thing in our society; they do not talk about abortion because it’s not a good thing that you are educating young people about hospitals or services. It is not seen as something good. So, we face a lot of problems and a lot of hurdles, but we work together.

Speaking about our principles and values at Mashal Girls Foundation – we work together, we sit together, and the five-six members all make decisions, and then we collectively try to get something out of that decision, which is fruitful for the community and also for the female members and adolescent girls of the community with whom we were working.

If I talk about the needs, first of all, we need comprehensive information. This is something that cannot be done without information, so we need age-appropriate, cultural information abouts sexual and reproductive health and also safe abortion methods. We also need information about access to services, because we face a lot of problems regarding that – mostly because people do not help us. Because in our country – I don’t know about other countries but in ours – in our hospitals, there is no place for abortion. They do not give you an area where you can come and seek abortion. It’s prohibited in our country. So, we need medical facilitation that gives us a safe abortion place. The third need is stigma reduction. Creating awareness is something big, like we will first create awareness about menstrual hygiene, SRHR and safe abortion – we will go to people and we tell them that we are not doing something wrong, we are doing it for safety and life, because abortion is not something easy – if are doing it incompletely or doing it without safe medical facilities, it can be something very dangerous, I would say. So, stigma reduction is a need that is big in our organization, and is one of our goals. The last thing I would say is that youth engagement is very important. If we are working in a youth-led organization, we must work with youth and also engage young people in advocating for their own SRHR rights and safe abortion and menstrual hygiene rights. So, if they can help us knowing their rights and try to raise voice for their rights, that will help us all a lot. That’s all I have to say from my side.

Shruti: Thank you, Sara. I think you really focused on how unsafe abortion can be risky, and safe abortion is actually very easy and it is very safe to do, but how laws restrict access to it. We will talk much more about this in the next panel discussion as well. Amanda, over to you.

Amanda: Thanks very much Shruti; it’s nice to be here in this space and to see some familiar faces and names as well. Thanks for having me join the panel. I think Sijan and Sara have touched on a lot of really important points, things that I also relate very much to and have thought about in my answers to this part of the panel discussion. I think we share a lot of commonalities in that when you’re in a youth-led organization or are running a youth-led organization, some of the most important values and principles are truly respect, transparency, empathy, and creating that connection that really connects us. I think being in a youth-led organization is such a unique experience in that everybody is going through something that’s very similar, right? The experience of being young, of being in SRHR and what that means, but it’s also such an individual experience – everyone comes from different backgrounds, and that experience of trying to bring everybody together can be really fulfilling and rich as a learning experience. I speak especially on behalf my experience being a part of For Youth Information, Kuala Lumpur, also known as FYIKL.

We are a youth-led organization working on bringing SRHR and safe abortion to the Malaysian landscape. Right now, we are based in Kuala Lumpur, as our name states, but we’re also trying to break that urban regional barrier.

With FYI,KL especially, when talking about what are some of our needs while working towards SRHR and safe abortion – something always comes up and is so important is funding. I think organizations that are already established really can help and stand behind us just by giving us funding and monetary support. We experienced this first hand when FYIKL had some amazing ideas to bring, but we really needed that funding, and that can come in a lot of ways – beyond just monetary support. It also means providing a physical space that we can have our events in, some of the names and connections – the networks that big organizations bring and already have. These were invaluable when we were getting FYIKL off the ground. We ran a series called ‘Abort the Stigma’ for three years. Each year ‘Abort the Stigma’ as a campaign had different ideas, and from the start we were sort of the youth branch of RRAAM Malaysia. It was so crucial at that time for RRAAM to be able to give us the funding, and that willingness just to share their resources and to have their support behind us really helped us take off. So, in that way, we were able to create a stronger bond between the few SRHR organizations in Malaysia that are working on the topic of safe abortion. And I’d say it was really successful and exciting; it was just an amazing experience to come together, and as a community be able to build stronger bonds.

So, I think that that does tie to what I want to speak about in terms of the values and principles that guide us, and that we also learned are really important to us, as a youth-led organization. I think I could probably speak a bit more to it later on when we’re talking about how to strengthen youth-led networking, but yeah, I just wanted to echo what see Sijan and Sara have already said and their experiences, and thanks so much again for having me!

Shruti: Thank you, Amanda! I think we can move to the next set of questions – How do you think youth-led networking can be strengthened regionally, and if you have any recommendations on making advocacy spaces more youth-led and youth-inclusive. Again, six minutes for each speaker.

Amanda: In thinking about youth-led networking and how we strengthen it, I think I would really challenge organizations to really listen to the youth. I feel like it can seem like it’s growing, which is amazing, but in some countries, it can also be such a small field that can feel very siloed. So, the challenge is for organizations that are already established – that maybe have international backing or international funding – to really listen to the youth in the country. If you don’t already have a youth branch, why is that? If you don’t have young people on your team, why is that? If you look at your leadership, the people on panels on your platform, if that’s not diverse and not inclusive of young voices, really questioning why is that and what are the barriers that are stopping your organization from platforming youth.

I think that coming into this work can be really intimidating, and it can often feel like it comes with really high barriers to entry. I think young people know so much from lived experience about what it’s like to be young, what it’s what are the challenges to access, what are the challenges in advocacy, what are the challenges in speaking on things that matter in SRHR and safe abortion; and I think organizations would really do very well to listen to those voices and experiences. So that would be my challenge and, I guess, question to organizations. Even panels like this help in getting the word out in really asking organizations and leadership – people who put money behind this work – and asking what they value and what it is that should be valued.

Something that I can recommend from experience in making these spaces more youth-led and inclusive, again going back to our experience with the ‘Abort the Stigma’ campaign we did – we’ve had personal experience in going up against these high barriers of entry. So, what we wanted to do was to reach out to the community itself. What we did was, we created a podcast series in Malay – it was more colloquial, it wasn’t formal, like not a more formal brief like research papers. Those are really important as well, of course, but can be so hard to break down and explain. So we did it in more colloquial speak; we had members on Twitter interacting with local users of Twitter who had questions about safe abortion. We looked into hashtags, into keywords, that would lead us into maybe threads or questions that were already ongoing with young members of our community, who were asking really important questions but weren’t being reached by resources and organizations that were already out there. That isn’t to say that we were the only people who are doing so – we had independent advocates for youth leaders in the community who are already doing that, so it was a really joint effort – building upon each other, talking to each other, and seeing what it is that we could build upon and make stronger together. That really helped expand our advocacy. We have organizations on national level/ international level/regional level that are already doing some SRHR work, and really important work, like for example hotline work that we already do. So, it was just taking what’s already been done, and looking at how we can expand that to the youth.

With RRAAM, for example, we have the hotline which takes national inquiries for safe abortion access, and we brought on more young leaders – more hotline counsellors who were young, who were interested. Some of us had heard about it from the Twitter space itself, so there wasn’t necessarily even a formal recruitment process – it was more like coming in saying, “Hey do you want to be trained? We see that you’re already kind of doing this work personally and in informal settings; do you want to come on board and help us expand that even more?” That’s just happened last year and it’s already been pretty successful, and I’m really enjoying and appreciating seeing how our hotline team is growing and bringing new things to the forefront, and sometimes even challenging leaders who are there, and who have maybe done the work for 20-30 years. They may feel sometimes like they’ve seen it all, and I don’t blame people for feeling disillusioned – I have experienced that many times – but again, you know, just bringing fresh perspectives and coming up and asking questions and saying, “Hey, you know we’ve done this many years; how do we expand on that? How do we change that; how do we shift that a little bit?

I think any sort of shift is always in the right direction, especially when coming from the youth. Trusting their voices is so invaluable, more than what any other formal setting or training could give. So yeah, in short, just listening to each other, valuing our voices, and building community from that in a really organic way, I think, is so important.

Shruti: Yeah thanks, Amanda; I think you brought in some really important points which relates to challenges that young people face, and how actually youth advocates are kind of aware because they have lived experiences which are very similar. I think those are some very important points, and you also said something about being siloed, which happens a lot in advocacy spaces. So also questions on how can we create more spaces where young people are heard, but they’re also not siloed within the mainstream agenda such that where all adults are there and young people are siloed. I think those are some important points that relate to inclusivity as well.

Sara: Yes, if we talk about the strengthening of youth-led organisations, it is a multi-faceted approach, like leverage to technology, local resources and collaborations. Moreover, to make advocacy spaces more youth-led and inclusive, there are some recommendations that can be considered:

Digital connectivity. Youth from different areas can utilize online platforms, and they can share their experiences and strategies about working on SRHR and safe abortion in their areas, so the other person can also relate some time or sometime they can gain experiences listening to other people from other areas too. Second, I will talk about local empowerment. If we organize local seminars, local events that bring the local youth and youth-led organizations together to discuss SRHR and abortion issues, fostering a sense of belonging and ownership. Training and capacity building is also something that can strengthen youth-led organizations. If we can provide training on leadership skills, communication, negotiation and advocacy techniques, also cultural sensitivity in area like ours in Pakistan. So, to tailor advocacy messages to align with cultural norms and values is something very important. Another thing which can strengthen youth-led organizations is mentorship. If we can establish mentorship programs and connect the youth to the mentors so that the experienced activists can give them much better ideas and share their experiences with them, to transfer skills of development and knowledge. Youth participation in decision making is also something very important for youth-led organizations. If there is an adult in a youth-led organization and that person says, “No, I have made a decision and you have to work on that”, this is not something that would work in a youth-led organization. We have to give the space to the young people to talk about their experiences and give them a space for decision-making.

These are some things that can be helpful for strengthening youth-led organizations, I would say.

Shruti: Thank you Sara; I think you also mentioned quite a few important points which relate to developing advocacy and leadership skills of young people, which is so important in SRHR spaces because it is related to cultural norms, like you were saying, and it is so closely related to cultural sensitivity. So those are really important points. Moving on to Sijan; Sijan, over to you.

Sijan: Thank you so much, Shruti. I think Amanda and Sara have mentioned a lot about how we could strengthen and what are the recommendations that we could carry forward to ensure inclusive advocacy. Adding on to this, if I have to say how we could strengthen the network of youth-led organizations in our respective countries – I think one of the major things that we can do is embrace our own advocacy journey. Because, all of us have different advocacy strategies, methods and mediums, and different ways of modalities of how we actually work and what we actually try to do. And one major step that we could start while we try to strengthen the entire coalition of the youth-led network is embracing how we run the advocacy processes because there could be flaws – there could be good as well as bad things that we might be doing, things that we could be improved. The entire coalition starts to get stronger when we start to appreciate each other, and when we start inviting each other to spaces where we can hear each other’s opinions, and have a safe space where we could have a very active conversation. I think that is one of the major things that we need to do more, because there are so many youth-led organizations and we do not have a common platform to talk about certain things that we all believe and do.

And the next way I think it could be strengthened is: When we are working as young people on certain topics like SRHR and safe abortion in developing countries like Nepal, there are often a lot of oppositions. The opposition could be the government, it could be our own close people, it could be other organizations who do not believe in your beliefs. And at times, when we see oppositions, we tend to get disheartened. We are young minds who are trying to do certain things, and when we see someone actually opposing or not hearing us at all, it does actually feel bad and sometimes there are days when our morale is really down. I think when this happens, one thing that I try to do myself also is – embracing oppositions as well. If somebody is talking about it, it means you are actually doing something, and what you are doing is actually creating impact.

While we are talking about oppositions, I want to say that as young people leading youth-led organizations, sometimes you are your own opposition. This especially happens with young people that we are trying to mobilize in our community, because today they might feel like they want to work for SRHR and tomorrow they might have another interest that they feel they would want to invest in. And when that happens, you don’t really want to stop it because you know how young minds work, you know that your interests and choices are flipping every second, right? So, I think we all can strengthen the entire young people’s coalition by just embracing that sometimes. Because there are a lot of times you really cannot do it anything about it – you cannot put someone on conjoint and say “okay, you have to be around the kids you have to talk about safe abortion.” We cannot do that, so I think the beauty lies in actually embracing everything that we’re doing, and that helps us strengthen so much on what we do.

Also strengthening the network does not mean only within your own country, because when it comes to safe abortion and SRHR, a lot of regressive laws continue to be passed in a lot of countries. If we keep silent on the regressive laws that other countries pass, then there’s no point in strengthening young people’s coalition. It is not only my country or your country, at the end it should be a movement. Safe abortion or SRHR should not be your country specific or your area specific. I think that’s where the entire power of young people, the choices and voices of young people, would be so evidently visible to everyone.

I have very few recommendations that I really would want to put out here to make advocacy spaces more youth-led and inclusive:

The first one is, diverse youth should be involved in the decision-making process. When we talk about decision making process, that could be within the organization or outside the organization, but it should not be just to tokenize the young people but their voices should actually be heard. A lot of times we’re just tokenized, but then the question is if our voices are actually being embedded somewhere when the laws are being formulated, when programs are being designed. I think this is something that we need to keep ourselves accountable – whether our representation is making any sense, and we also need to keep agencies accountable, whether that be the government, our NGOs, our partners, our stakeholders. We need to make them accountable as well – where are our voices? We spoke about this, where have you embedded it? I think this is very important, that we take the question and we question every other person every time you feel like questioning.

And another thing – I think we’ve discussed this in the prior question as well – with everything that we do, one thing that is essential to make the youth-led spaces safe and inclusive is empathy. Because, while we’re working on especially young people’s SRHR, you hear a lot of stories, and a lot of times you would want to say a lot of things to the person but you cannot tell because you understand where the person is coming from. So, if we lose our empathy as a youth-led organization, I think we lose our charm as well. So, this would be one recommendation that I think is very important for us to carry, because once we start empathizing, we ourselves would go into the inclusive path of an advocacy journey.

Finally, obviously an intersectional approach is something that we need to take. A lot of times we miss out this because we are time-bounded as well, because we have to complete certain work in certain time and we cannot always bring everything on one plate, but intersectional approach will always help us out if we embrace it the best as we can.

I think that’s all I have to say on how we can be louder and prouder as a youth-led organization and as young people working in the development sector. I now pass over the space again back to Shruti.

Shruti: Thank you, Sijan. I think some of the important things that you mentioned are first to have networks of organizations which are youth-led, and I think there are very few networks like that. So having those kinds of spaces to learn from each other, and something you mentioned earlier also that that those networks should have young people who lead the movement actually. And also having learning exchange sessions with people who are more experienced, who have probably done something very similar – having those learning exchange spaces is important. Even for YANAA, for e.g., it’s very important for us to create those spaces for young people and also have young people as somebody who has the knowledge of informing and influencing. So those are very important points.

OPEN DISCUSSION/QUESTION AND ANSWER SESSION

In this session, the participants discuss the following questions, posed by Laxmi and Nurul respectively: (a) How can we make youth organization coalitions stronger and make our work more sustainable? (b) In what ways can we challenge the assumption that certain strategies have been exhausted, and how to brainstorm to build on existing foundations? How do we measure the impact of our efforts to bridge the gap of between the established advocacy and then utilize our engagement, and what can we use to assess the effectiveness of these initiatives?

Sijan: I think I would want to take that as well; if any if I miss out on anything the other panelists can join in. For the question that Lakshmi has mentioned, how can we make our youth organization coalition stronger, I think we need to have a regular communication channel. Even if we cannot communicate on a regular basis, like for example today we have this event organized by YANAA and we all are invited, we all are young people and we’re trying to talk about things. We’re just trying to bring everyone together in a platform, and like this we’ll meet once, we’ll meet twice, and then once we start seeing the same faces again and again so many times and in a lot of spaces, you eventually connect with the person and you eventually connect with their work as well. I think this is one of the small steps that we can take – in actually highlighting what the other person or the other organization might be doing. So just having these common spaces, inviting each other to join these spaces, and just uplifting whatever we all are doing together – I think that’s one of the major steps we can take to make the coalition stronger.

And talking about making our work sustainable, this is I think a very big question that we all have – whatever we’re doing, is it sustainable or is it just momentary? I think, for me, if you ask how we could make our work more sustainable, I would say we need to focus on making our target group as beyond just our primary beneficiaries. For example, YUWA works with young people and for young people, so we basically work for young people’s SRHR. We do a lot of awareness sessions, a lot of discussion spaces with young people. However, while young people are our primary beneficiaries, these young people’s lives are again attached with so many other beneficiaries, for example, their schools, their teachers, their parents, the society… so we have a lot of secondary and tertiary beneficiaries that we have to touch if we want our primary beneficiaries to actually have a behavioural change. It would be a very long process to tap into every other step of beneficiaries we could reach, but maybe a small step could be that while we’re reaching to young people, we could reach out to their parents as well, we could reach out to at least to their schools or to the coalition of teachers that their school/college has, since young people’s decisions are mostly controlled by these primary and tertiary beneficiaries. So, if we could make an impact on those other people, I think that would make our work more sustainable and we’ll actually be able to see changes.

That is all I have from my side; if anybody wants to add, I pass on the space to you.

Amanda: Adding off of what you have mentioned already, Sijan, a word that constantly came to mind was ‘continuity’; the ability to be able to continue the work that we do within organizations, and this is in establishing maybe stronger member basis, stronger ways to create a wider reach, making sure that leadership is transparent and that we’re able to pass it on when we need to. Being young means that these lived experiences are always changing so quickly and our experiences are so diverse as well, so making sure that we’re always being aware of that and being open to that as well, is important. Also important is making sure that the older generation is open to younger people coming in, so that continuity ensures that SRHR is thriving and advocacy continues to grow in the places that we’re at. This is a problem that sometimes we face as well here, and we’ve learned that we need to continually have new people join and be introduced to SRHR scene, and that they feel welcome and feel like they can come in. Even if folks might not know necessarily everything off the bat and they never will, but making sure that there enough trainers on board, enough people willing to share that knowledge openly and generously.

Also important is never underestimating the importance of digital spaces; we now know from the pandemic that digital spaces had to grow so much and a lot of people have become much more well versed in traversing zoom landscapes the way we are right now. So never underestimating that social media – how we’re able to use that to connect there in order to make this work sustainable.

Vinitha: Yeah, I think while we’re creating spaces for youth networks, one of the challenges that we face building cross-movement solidarity. When we speak of young people, it’s not a homogeneous group. It has a lot of people from various marginalized identities and different sets of identity that that may have similar experiences that we live, but also might have very different experiences as well. So, in order to strengthen those spaces, it is very important to have marginalized young people in those spaces –especially when we speak of intersectional movements, that also touches upon different issues that young people face, so in that sense, people especially from marginalized spaces find decision making spaces or leadership spaces very hard to find. Hence, we as young people who are leading movements, who are thinking about very important issues, should also think about prioritizing on making those decision-making spaces for young people who are from marginalized spaces themselves. That enables more trust in the space that we engage in, and also ensures that there is more space for building cross-movement spaces, and push the cause in an intersectional way.

Sara: I just wanted to add to what the other speakers said, that if we want to make youth organizations stronger and sustainable, one thing which is most important is that we should be ready to change our plans. So, in times when we think that we need to change our plans or that we need to change something in the decision making, or in our teams, we need to go ahead. We should not be change-averse, because that is something which is not going enable the sustainable growth of our organization.

Shruti: Thank you, all. I think, what we were saying in the beginning, that even for us to organize this meeting, it has taken a lot of planning. So, I think it’s very important if you want to sustain youth-networking that we remember that it is on us – it is not people from the outside who are going to enable any of this, or who are going to organize any of these meetings. So, I think communication channels are very important, and it’s also very practical in terms of getting us together and having us having a platform where we can talk about issues that relate to youth-led organizations. Especially since this question also came up about sustainability, that is something we have also taken into account and we will be talking more about this in the agenda tomorrow. I just wanted to say that, and some of the important things that of course came from this discussion also is that, youth groups are not homogeneous – they are very well diverse – and how do we make youth spaces more inclusive, not just for young people but also for marginalized young people. That is something that as youth-led networks we need to remember. So, thank you for bringing in that point about sustainability and diversity, homogeneity, etc.

Amanda: Thank you, Nurul. We have touched a lot upon organizational structure here, and in thinking about youth-led advocacy for this panel, it surprised me that my answers led a lot to organizational structuring and how that’s so important. I think sometimes it does need a little push – it could be gentle, it could be knocking it down – in thinking about how we sometimes can assume that ways working have already been exhausted, like we’ve done it and there’s no new way to do it, or we’ve done it and it doesn’t seem to be working. Those feelings of frustration and hopelessness a lot of times come up in our SRHR advocacy and work, but in building those networks and interlinkages there’s so much inspiration that we can take from each other, that cross-movement solidarity that Vinitha really importantly pointed out as well. I can also share that in our hotline work in Malaysia we actually even take so much inspiration from Samsara. The ‘Abort the stigma’ campaign, our very first one, was an art exhibition that actually came from the Samsara House of Silent Voices, if I’m not mistaken. I think somebody from FYIKL had visited and had come back with so much inspiration, and we were able to work together with ASAP and with RRAAM to come up with something similar of our own, and from there we got the ball rolling for the next three years for the ‘Abort the Stigma’ campaign.

So, for me, it was a really amazing example in real life in real time of how cross-movement solidarity can be built, and how the youth voices that we brought to the center within FYIKL were able to create something really fresh and new within the SRHR and safe abortion space in Malaysia at that time. And I think that will continue to be replicated over and over again. This trend of maybe pushing on things that can seem like they’re so set in place or that there’s no new way to do that, or people assume – especially sometimes in leadership – that this is the way we’ve always done it and this is the way we have to do, because that’s just what we know. But we know from our experience that it doesn’t have to be true at all.

It’s a really important question and thank you for voicing it, and also even just the ways in which we continue to inspire each other as we come into conversation together and just learning from each other – it’s so amazing to me and inspiring all the time. So yeah, thanks, Nurul.

Sijan: Can I add something to what Amanda has mentioned? Because I think Amanda has covered so much of everything that was asked for, but I would also want to add a bit on specifically on the solidarity part and on how we could deal with oppositions. This is something that we recently have had discussions in our office well, because a lot of times when we talk about opposition, we think of those who vocalizes against. But there are also oppositions who would not really tell us anything, but sometimes silence is more dangerous than people actually opposing us right in front of our face.

I could actually give you an example of what happened in our office. During pride month, what happened was our communication department published a video on TikTok. We try to engage a lot of social content in this movement on TikTok because a lot of young people are right now very active on TikTok in Nepal. So, when we had this pride parade in Nepal, we asked the attendees of the parade about what’s their viewpoints on LGBTQIA+ community, and it was a very well put video where people just shared their opinions. But the comment section was full of hatred. It was so full of hatred that one our content creators even got personal messages in regards to publishing the video, about just asking people what’s their viewpoint. So, we could actually imagine the opposition could be this as well.

While we’re dealing with it, a lot of times we tend to directly answer like, okay, whatever you were telling is wrong and whatever you were trying to impose on us is something that we don’t believe in. While this is important and sometimes we have to be direct as well, but most of the time I think we need to take the process very slow while we are dealing with the opposition and creating a solidarity among us because we want someone to believe in what we are doing. We don’t want to force someone to believe, rather we want someone to actually acknowledge whatever we are doing and then only put their belief in us.

When we received so much hatred in the comment section, we had an option to ignore and we had an option to actually deal with it. So, what we did was, we created another video addressing the comments, because that was also an achievement for us – people coming to our video, people actually portraying that they don’t believe in this entire concept and they think that it’s all just a nuisance that we’re trying to create when we’re celebrating pride month. We took it as an achievement because people were coming telling us things and then we are addressing it, we got pretty happy about it, because the video reached to the right audience. So sometimes, like I mentioned, embracing opposition is the only option that we have, and while dealing with it I think we have to be the better person. We have to be a bit calmer; we cannot directly tell them that “okay, no, you are wrong”. We really cannot do that because sometimes the opposition could be more powerful than us; they we might be important for our movement in some way. So, I think that is something that we need to be very careful while we’re trying to create a movement or dealing with any opposition in our own spaces.

And talking about solidarity – on talking about how we could do that or how we could build a movement together – I think it’s very simple. If something regressive happens in Nepal, I would want other advocates who are working in other countries to also vocalise for Nepal. And same goes for all the advocates working in Nepal as well – if something happens in India, Malaysia, Indonesia or any other country, it is our responsibility to talk about that as well. Just because I am not a citizen of that country doesn’t mean that I am not liable to talk about it. When I say that I am a young advocate, I don’t belong to a particular country but I belong to a movement. So, I think we need to see it like that as well, and that is where the entire conversation about solidarity begins. That is all I wanted to add, and thank you so much for such an amazing question – it made me question a lot of things and made me realize that there are a lot of things that we need to look into.

SECOND PANEL DISCUSSION – NATIONAL LAWS, ACCESS AND OPPOSITION

(Facilitated by Indah Yasuri, Programme Officer, ARROW)

In this discussion, the speakers were first asked to introduce themselves and the organisations they represent, and then answer the following questions: What are some of the laws and policies related to safe abortion in your country? What are the challenges of access and opposition that you encounter?

Indah: Hello everyone; before we continue to the next session, I want to introduce myself first: I am Indah Yasuri, a programme officer at ARROW. I am working remotely from Indonesia, and ARROW itself is Asia-Pacific Resource and Research Centre for Women. The organization is based in Kuala Lumpur, and we work on women’s health, sexuality, sexual and reproductive rights, and also empower women to information, knowledge, engagement, advocacy and mobilization.

I will be the facilitator for this panel. In the panel we will discuss about our experience related to laws and policies and access to safe abortion especially for young people. And we will talk about the challenges and opposition to access in each country of the speakers. In this panel today, we have four amazing young activists from several countries:

We have Kazuko Fukuda from Japan, Sarryna from Philippines, Priskila from Sri Lanka and Laxmi from Nepal. Welcome everyone; I would invite everyone to introduce themselves before we start the discussion. You can share your names, your organizations, and also maybe you can share with the participants three things from your organization that everyone should know about.

Priskila: Hi everyone, I am Priskila, I am from Sri Lanka and I work with the youth advocacy network in Sri Lanka. Three things that I would like to share about us are: (a) We are a youth-led organization working on safe abortion and SRHR in Sri Lanka. (b) We are the only youth-led organization which is solely focusing on reproductive rights in Sri Lanka. There are many other organizations which work on reproductive rights, but we are the only youth-led organization which works with volunteers focusing on SRHR and reproductive justice in Sri Lanka. (c) Another special thing about our organization is we always look at disability accessibility in our work on reproductive justice, and we make sure that whatever we do is disability accessible. We have special programs for people with disabilities running within our organization.

Kazuko: Hello, thank you so much for having me here today. My name is Kazuko Fukuda, from Japan, and my organization is called #Nandenaino Project, which means “Why don’t we have” in Japanese, and we are also a youth-led organization. Our members have so many different kinds of expertise – from social studies to being a student for becoming a doctor, and also, we are focusing on advocacy work for access to SRHR in Japan, especially for young people.

Sarryna: Hi, good afternoon, I am Sarryna, a Women’s Global Network for Reproductive Rights (WGNRR) networking officer. Three things about the organization I am currently in:

- First, WGNRR is a network registered in the Netherlands but its current organization office is in the Philippines, which is why I am here.

- WGNRR works with young people, and as part of its youth program, what’s vital was the establishment of Young Advocates for SRHR, of which Mark Devon, one of the speakers, is a part of.

- The third thing is that WGNRR also helped in the establishment of Philippines Safe Abortion Advocacy Network in 2015, together with Center for Reproductive Rights. That’s it for now; thank you!

Laxmi: Hello everyone, I am Laxmi from Nepal, and I represent YoSHAN, which is a organization actively working on sexual and reproductive health rights. Three things that you have to know about our organization is that our organization is women-lead; it is a feminist organization and we work for body autonomy of all people. So the three keywords are: women, feminists, and bodily autonomy.

Indah: Thank you, I’m really happy that can be a facilitator today in this session and that I could meet all of you. So, like I already said, today we will talk about experience related to policies and access to safe abortion in in each country as well as the challenges and the opposition that happen in each country. I want to give this floor to our speakers. Sarryna, do you want to start the presentation first?

Sarryna: Okay. I know that this panel is focused on national laws, the opposition, and I was actually tasked to discuss the backlash in the Philippines in the context of safe abortion. I don’t want to focus only on the backlash or the negative side of our work in the safe abortion rights advocacy, so I still wanted to like put on a better picture of what we’re also doing despite the fact that we still continue to face backlash in the Philippines.

We know the Philippines remains one of the few countries in the world where abortion is prohibited altogether. This really makes us face lots of challenges even when it comes to having open conversations about abortion till now. There are highly restrictive abortion laws in the Philippines, and that creates three challenges for us as safe abortion advocates.

The first one, which is very obvious, is the very limited funding for safe abortion advocacy. We also as an organization experience this one, since some of the founders or donors that we tend to talk to are really quite hesitant to include safe abortion advocacy when it comes to funding for projects. So, we always have to – for the lack of a better term – “sugarcoat” on how we can create projects that can actually also include safe abortion rights advocacy.

Despite the illegality of abortion in the Philippines, post-abortion care, however, is legal in the Philippines. But, since in the term ‘post-abortion care’ there is still the word abortion in it, even for projects relating to strengthening the post-abortion care policies, it makes it difficult for us to get funding for these kinds of projects as well. So, it’s not really just about the general policy advocacy work that we’re doing that has a lot of challenges, but it’s also about how we can actually sustain these kinds of efforts and initiatives that we have been building to continue the work for safe abortion advocacy, and even for the strengthening of post-abortion care policies in the Philippines.

This takes me to the next backlash or restriction that we are facing here in the country – the challenging policy advocacy in the country that criminalize abortion. The reality in the Philippines is that even post-abortion policy gets very limited funding or support for strengthening its implementation, even at the national level. And second, there is continuous and high stigma about abortion as part of everyday conversation in the country. Hence it becomes also difficult for us to look for champions who can actually openly support the campaign against the criminalization of abortion. This is one of the things that we are focused on at WGNRR and partners when it comes to safe abortion work in the Philippines.

And lastly, the high stigma in the conversation about abortion restricts advocates to express public support, because they fear for their safety and security. So those are main limitations that we have. However, I want to take note that human rights defenders continue to fight for safe abortion rights in the Philippines, especially in relation to the campaign against criminalization of abortion.

This is not exhaustive; it is just an overview of what WGNRR does in the Philippines when it comes to the work for safe abortion rights. WGNRR is part of the ‘September 28 working group’, which I think some of the organizations here are also part of. The goal is the September 28th International Safe Abortion Day Campaign. WGNRR works at the global level, but also at the local level, which means that WGNRR has programs, activities and initiatives in partnership with local organizations and local groups such as Philippines Safe Abortion Advocacy Network (PSAAN) that openly advocates and creates conversations campaigns about the criminalization of abortion in the Philippines.

Apart from this huge effort of policy advocacy the WGNRR or PSAAN do, we also conduct direct community activities and partner with the grassroot community such as in the urban poor sector or with the youth sector, or women in employment sector. We conduct learning sessions on sexual and reproductive health rights, and we also conduct abortion stigma elimination workshops, with the goal to facilitate conversations on how to create a safe space where is abortion stigma can be analysed and thereby reduced at the community level.

And lastly, of course, in creating conversations on why is it also important that whenever we talk about safe abortion rights in the Philippines, we also include the discussion post-abortion care policy. Because, these kinds of limitations that we are facing in the Philippines, we always see a window of opportunity to advocate and to include the criminalization of abortion campaign, by creating conversations also on the importance of strengthening post-abortion care, as that is the only legal care in our country.

I think that’s it for now; those are just an overview of what we are doing and the limitations or the challenges that we are facing, but I would like to end the discussion on a very positive note. If you have any questions, later on I think we have time for the questions. Thank you!

[Sarryna’s PowerPoint presentation can be accessed here.]

Indah: Thank you Sarryna; I can already see some questions, but please keep them for later as I want to invite the next speaker: Kazuko, do you want to start? Thank you!

Kazuko: Thank you so much everyone. Again, I am Kazuko Fukuda from Japan, and I am co-founder of #Nandenaino Project. I have advocated for SRHR services in Japan including the DSV, contraception, and safe abortion after coming back from studying abroad Sweden. To do that, we have done a lot of other advocacy work including online petition or lobbying, and have done a lot of research and awareness raising, lectures, etc. If you’re interested, please look at the website.

Today, I would like to share the situation of abortion in Japan; maybe some of you have already heard that Japan has finally approved the use of abortion pill this year, but actually there’s tons of difficulties and also opposition especially from the politicians and also the Society of Gynaecologists, so I would like to briefly explain about what’s going on in here.

First of all, in Japan, we still have the criminal law against abortion since 1907. Because of this law, the women who has done abortion by herself can be imprisoned for not more than one year. But at the same time, we have another law called Maternal Health Act from 1996, which allows women to have abortion in certain conditions. So, when women have a physical problem or economical problem or when they are raped, then they can have an abortion. And we don’t have to show the like history of bank or something, so most women use economic reasons when they ask for abortion. So, in a way, it’s quite accessible but there are different the problems here too, because the doctor who can give abortion is only by ‘designated doctor’ who are kind of especially trained by the Society of Gynaecologists. Also, the biggest problem here is that you need consent from the spouse when you get an abortion, which means that the final decision maker on having abortion is the spouse and not women. There are cases where women cannot have abortion just because they cannot get the consent from the spouse, and all the hospitals deny those women access to abortion. Based on the law, you don’t need consent if you are single, but then many doctors are afraid of being sued so you are required to have consent anyway from the partner or the parents. So, it’s really problematic here.

Under this condition we have about 126,000 abortions and the numbers are decreasing. There are many reasons, but mainly because we are having a smaller number of women in reproductive age so that’s the biggest reason.

There are tons of problems in the way to have abortion to in Japan as well. First of all, the price of abortion is about $1000-2000 which is certainly not accessible especially for young people, and there’s no insurance that covers it at all, while most basic health care is covered by the National Healthcare Insurance in Japan. So that increases a stigma I guess, because it is saying that abortion is not necessary care. And the reason why we have this high cost is that we had D&C, which is otherwise considered as unsafe abortion by WHO. This is the reason why we only allow designated doctors to give abortion, because more than 80% of doctors in Japan still use D&C and not, for example, MVA and or abortion pill which is safe portion. MVA was approved in 2011 or something, but then because it’s only for one time use and is very expensive so that’s why very small number of clinics use it and still depend on D&C.

And finally, we have abortion pill this year but then there are so many problems around it to when it comes to its access. First, the Maternal Health Act is active for this case too, so abortion pills can also be provided only by designated doctors again, and also you need spousal consent to have a pill. And the time limit for abortion pill is as short as nine weeks in Japan, so there is a possibility that you will not make it in time. And secondly you will be hospitalized when you use the pill. While usually you can take the second dose of abortion pill at home or where you feel comfortable with the private toilets, but in Japan the government decided to force women to be in the hospital until everything is done. And if it’s not done by the morning, women are forced to have a surgery anyway. So that’s why, the price is the same as the surgery – it can cost $1000 to $2000 for abortion pill too. So again, it’s really not accessible at all.

The reason why like after 30 years of abortion pill being widely used, finally in Japan the usage of pill is approved because the profit of the gynaecologist is kind of still protected. So that’s why it’s quite a big issue. This also shows the attitudes of Japanese government towards abortion which was highlighted in the review at the UN this year. Some country pointed out the problem around abortion in Japan, and the answer of the government is that abolishing the crime of abortion and making it unpunishable requires careful consideration, because the unborn needs to be protected as living beings and disrespecting them can be equated to disrespecting human life.

The Maternal Protection Law stipulates the necessity of spousal consent when performing an abortion, but it’s a difficult issue that is deeply related to individual ethical and moral views. The government believes that it is important to deepen discussion at all societal levels regarding the appropriate provision of the Maternal Protection Law, and the main ruling party is deeply connected to the conservative religion which supports them very well. So that’s why those conservative religions are really going against the access to abortion pill. So together, this government and the Society of Gynaecologists, create the profit from abortion. It’s really not easy to make it accessible for women.

In addition to that, access to contraception is really not easy in Japan still. Implants, female condoms – those are not approved to be used so it’s impossible to have it in here. AUD usually cost $500, pills cost about $30 per month, which is not affordable again for young women especially. And for emergency contraceptive pill in Japan, you need a prescription and it costs about $100. We have fought against it a lot, but it’s still very difficult because like the Society of Gynaecologists are really against it as they are afraid of losing their profit of abortion because of this.

This is not something random, but historically women’s health has been neglected in Japan. For e.g., Japan was the last UN member which approved the use of the pill which happened in 1999, while viagra which is used by men was approved to be used in 1998 even if it was newly created in US and so many men die because of viagra. At that moment, the government got a lot of like criticism from inside and outside of Japan, which is why finally the pill was approved in 1999. The reason for all of this is I guess the male-dominated politics in Japan. There are only two women in the cabinet, and among national politicians we have only about 10% of female politicians. In local council also it is dominated by old men – like 85 five percent of them are male, and 56% open more than sixty years old. When you see reproductive age women, like in their 20s to 30s, that’s less than 1%, and there are only like 15 female politicians in 20s out of 30,000 local politicians in Japan.

So, although I have worked for like five years in Japan, I have always felt that it’s difficult to bring our voices because no one can really understand and listen to us as they’re not able to understand what young women usually face. So that’s why I have started another organization called ‘Fiftys Project’ with my colleagues to help young feminists be local politicians. If you’re interested in that please look at that project, and if you want to see more information about Japan, there is a leaflet that we create, so please look at that. Thank you so much for giving me this opportunity!

[Kazuko’s PowerPoint presentation can be accessed here.]

Indah: Thank you so much, Kazuko. I would like to move to the next speaker; Laxmi, would you like to go next?

Laxmi: Hello everyone, I am Laxmi Choudhary, and I work at YoSHAN which is a youth-led organization. We are actively working on safe abortion advocacy here in Nepal. In this presentation I will be talking about the history of abortion services and advocacy in Nepal along with challenges faced by advocating organizations. Nepal is regarded as a progressive nation in terms of safe abortion policies, and currently we are following the Right to Safe Motherhood and Reproductive Health, 2018, which has defined abortion as the act of foetus coming out or taking the foetus out of the uterus before being born naturally, and abortion services are performed by licensed health institutions, licensed health workers upon fulfilling the process mentioned under this act.

For a very long time like other nations, abortion was generally banned Nepal under any circumstances, even if the women’s health was at risk, due to which unsafe abortion practices were high. Unsafe abortion practices like use of unknown herbs and some instruments to end pregnancy was common practice. And due to this the complications were very severe, and resulted in increased maternal mortality as well. And as abortion was generally criminalized, there were cases filed against women for seeking abortion services, and as a result some were convicted and some were even imprisoned. So, we can say that the law was very restrictive and it violated women’s rights as well.

However, after advocating for very a long time and after different international conventions on human rights and women’s health, Nepal finally legalized conditional abortion in 2002, and now safe abortion program is a priority program of the government of Nepal. The constitution of Nepal has also identified safe abortion as basic health service, as a right as well. In this figure [in the presentation], we can see that we have come a long way from legalizing abortion, to providing training to service providers, and development of Right to Safe Motherhood and Reproductive Health Act as well. This act has been a remarkable policy document which had been formed make necessary provisions on making motherhood and reproductive health safe, qualitative easily available and accessible, and in order to respect, protect, fulfil the right to safe motherhood and reproductive health of the women. Under this act, different conditions are mentioned under which safe abortion can be accessed legally or not. There are five conditions and it has divided into two justice family – so, up to 12 weeks, women can have safe abortion services with their consent. However, if the pregnancy crosses 12 weeks and up to 28 weeks, if the pregnancy is caused by rape or incest, or the pregnant person is suffering from HIV or any incurable disease, or if there are any defective features, or the pregnancy is harmful for the pregnant person, then as per the opinion of the health worker involved and as per the consent of women, they can seek an abortion.

However, apart from these conditions, abortion is criminalized and there are legal repercussions of seeking abortion services out of these of conditions. Within this condition even, abortion is punishable if it is sex-selective abortion or if it is done without the consent of the pregnant person.

In the journey of safe abortion developing policies, there are three country codes. In the previous country code, which was developed right after the legalization of conditional abortion, many things are similar to now, I would like to highlight on the differences: In case of rape or incest it was previously up to 18 weeks when it was allowed to safely abort in the health facility services, which has now been extended up to 28 weeks. However, while in the previous country code there was no time limitation for seeking several personal services if the life of pregnant women was in danger, but now in the in the current act it has been limited up to 28 weeks only.

Talking about the gaps that our current country law has, abortion has still been kept under the criminal law and it has been legalized under certain conditions only. Moreover, there is a very unclear definition of abortion and even in the legal documents also the definition of abortion also includes miscarriages, so it is not clearly defined. Seeking of abortion service has been limited up to 28 weeks only, and in the legal documents as well there is a very gendered binary language, which are some other problems. The word “pregnant women” is used so it’s not gender-neutral language.

Talking about the access to safe abortion service in Nepal, after the conditional legalization in 2002, National Hospital was the first ever hospital to provide comprehensive abortion services. So even though abortion service was legalized or safe abortion service was provided, people were unaware of legal acceptance or the penal provisions of abortion and lacked information about safe abortion services. As the people were unaware about penal provisions of abortion, in 2011, 57 women were sent to 26 prisons across the country. Even after 10 years of legalization, this was the situation.

In 2007, Lakshmi Dhikta versus the Government of Nepal was a remarkable court case that happened in which the Supreme Court issued directive order requiring the state to carry out the awareness programs, and it mentioned about the affordability of services as well. Since 2017, the public sectors are providing service free of cost, many service providers are trained now and the expansion of facilities are also happening throughout the country. As a result, maternal mortality has dropped from 539 to 239 per 1,00,000 births. But still, unsafe abortion contributes to 7% of all pregnancy related maternal deaths here in Nepal. And even though the service providers are being trained, service facilities are expanding, and services are provided free of cost, individuals in Nepal still face barriers to obtain safe and legal procedures. These obstacles include a lack of awareness of legal status of abortion, lack of transport facilities, gender norms that hinder women’s autonomy, and often the cost of the procedure and fear of abortion related stigma.

According to research done by Crehpa, 58% of all abortions in Nepal are still clandestine, i.e., abortion services are provided by untrained providers. And here, this is the data result of one of the demographic health surveys in Nepal, which shows that there is a difference in the safe abortion service utilization according to caste, ethnicity, community or economic background. Here we can see that abortion is lowest in Muslim religious people and in the Madhesi community, and is highest in the Brahmin and Kshatriya community. So, you can see that safe abortion service, even if it is free of cost, many people are not using it. Certain people of certain communities are still not being able to utilize the services because of the stigma around it.