In the past few months, before and after Trump took office, both Planned Parenthood in Washington DC and several private gynaecologists who provide birth control methods who were interviewed by the Washington Post have said that women have been visiting their offices more than usual specifically to ask about birth control. The data follow anecdotal evidence and speculation from the last months of 2016, after Trump advocated for policies that could change insurance coverage of birth control.

An increase in the use of IUDs and implants has been taking place for some time, but now women are worried about losing benefits. Since 2012, Obama’s Affordable Care Act has required that private health insurance plans cover prescription contraceptives with no cost-sharing for patients. Both President Trump and Rep. Tom Price, Trump’s appointee to head the Department of Health and Human Services, have vowed to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act. Neither supports a policy that would continue contraceptive coverage. If the Act is repealed, contraceptives could get a lot more expensive.

Other reasons include that the Congress is threatening to defund Planned Parenthood, who provide a large proportion of contraceptive services nationwide; he has appointed a vice president who has promised to restrict access to abortion, and now a Supreme Court nominee who could be hostile not only to legal abortion but also coverage of women’s health care. So a growing number of women want to do whatever they can to avoid an unplanned pregnancy at least during the Trump years.

Depending on the type of insurance women have, birth control pills can cost between US$160 and $600 annually, while IUDs and other long-acting reversible contraceptives can cost up to $500 to $1,000 for the initial insertion, but last for a number of years. Physicians, says Athena Health, have noted the financial uncertainty for women as health care policy shifts.

Among the commercially insured patients who make up 75% of the Athena Health sample, the rate of IUD-related visits rose by approximately 25% after the election, while for the Medicaid population, whose health care coverage would not change, those visits remained constant. But this evidence is only for the month of January 2017; whether the increase continues is as yet unknown.

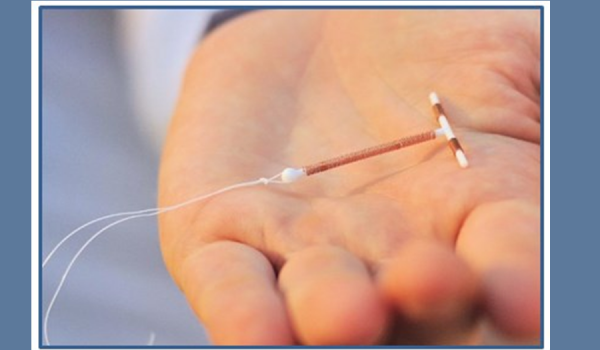

Washington Post, by Lisa Bonos , 7 February 2017 ; Athena Insight, by Chelsea Rice, 24 January 2017 ; VISUAL