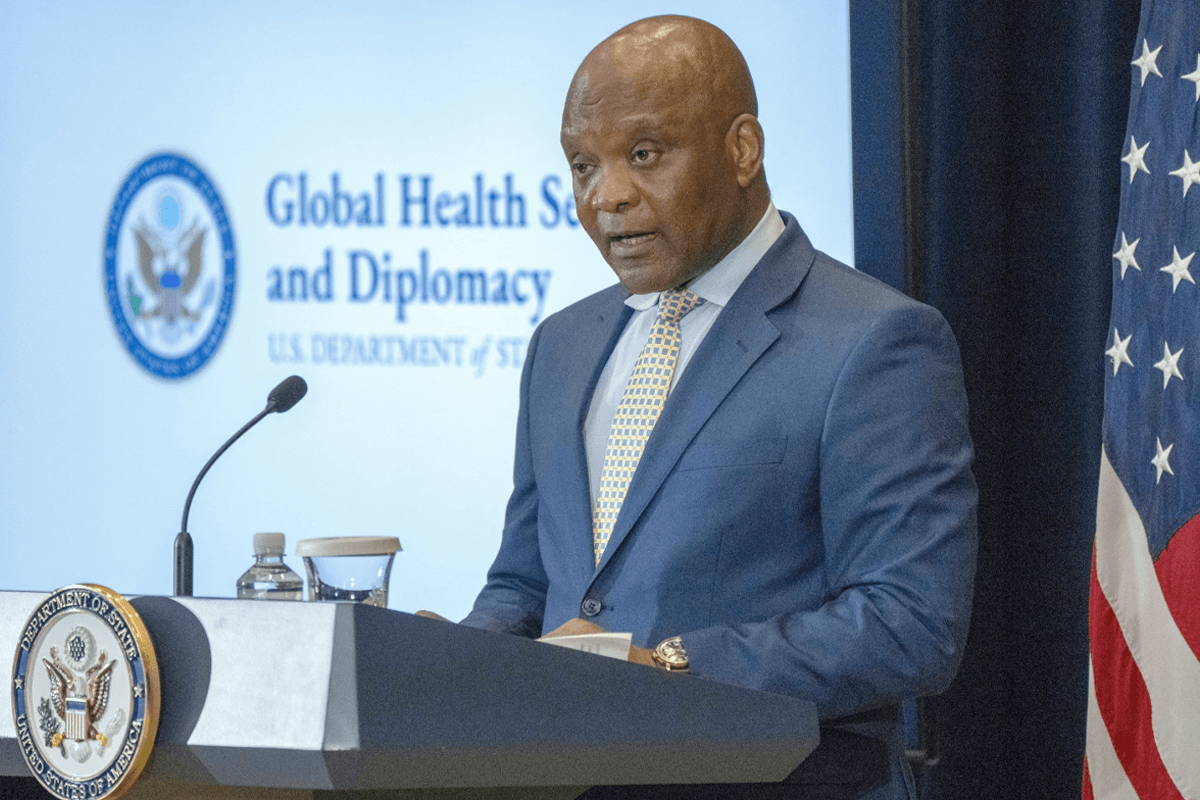

Image: Ambassador-at-large John Nkengasong, new head of the Bureau of Global Health Security and Diplomacy, US State Department

In Nairobi, Kenya, the graves at the edge of the orphanage tell a story of despair. The rough planks in the cracked earth are painted with the names of children, most of them died in the 1990s, before HIV drugs arrived.

Today, the orphanage is a happier, more hopeful place for children with HIV. But a political fight taking place in the United States is threatening the future of the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, the programme that helps to keep them and millions of others around the world alive. In August 2023, the State Department launched a new bureau aimed at making the battle against global outbreaks a lasting priority of U.S. foreign policy, and one of its key elements. But Republicans decided to try and sabotage the programme.

“Through PEPFAR, the US government has invested over US$ 100 billion in the global HIV/AIDS response, the largest commitment by any nation to address a single disease in history, saving 25 million lives, preventing millions of HIV infections, and accelerating progress toward controlling the global HIV/AIDS pandemic in more than 50 countries.” (PEPFAR website)

The reason for the threat — the anti-abortion movement.

The issue of abortion has been a sensitive one since PEPFAR’s inception in 2003. But each time the programme came up for renewal in Congress, Republicans and Democrats were able to put aside partisan politics to support a programme that’s long been seen as the vanguard of global aid.

But the bipartisan support is cracking as the programme is set to expire at the end of September. The trouble began in the spring, when the Heritage Foundation, an influential conservative Washington think tank, accused the Biden administration of using PEPFAR “to promote its domestic radical social agenda overseas.”

The group pointed to new State Department language that called for PEPFAR to partner with organizations that advocate for “institutional reforms in law and policy regarding sexual, reproductive and economic rights of women.” Conservatives argued that’s code for trying to integrate abortion with HIV/AIDS prevention, a claim the administration has denied.

In language echoing the early, harsh years of the epidemic, Heritage called HIV/AIDS a “lifestyle disease” that should be suppressed by “education, moral suasion and legal sanctions”. It recommended halving US funding for PEPFAR, saying poor countries should bear more of the costs.

Shortly after that, US Representative Chris Smith, a longtime supporter of PEPFAR who wrote the bill reauthorizing it in 2018, said he would not move forward with reauthorization this time unless it barred non-governmental organizations that used any funding to provide or promote abortion services. He said he came to this decision after having extensive conversations with stakeholders involved.

Because that proposal faces stiff opposition from congressional Democrats, Smith, with support from prominent anti-abortion groups, wants to cut PEPFAR’s usual five-year funding to one year if that ban is not included. He said that way, the programme would remain funded at its highest level — $6.7 billion — while allowing lawmakers to annually revisit contracts with partners they believe may support or provide abortion services.

But supporters of the programme say that under existing US law, partners are already prohibited from using its funding for abortion services. The head of PEPFAR, John Nkengasong, told the AP he knew of no instance of the programme’s money going directly or indirectly to fund abortion services. Born in Cameroon, Nkengasong was a founder of the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention operations in Africa. He helped set up some of the sub-Sahara’s first sophisticated labs for work with HIV and AIDS.

He warned that any instability in the flow of U.S. funding for PEPFAR could have dangerous implications for health globally, including in the United States. The key to controlling AIDS, he said, is the assurance that infected people have a pill to take each day. Without that, the virus could come back, and about 20 million lives might be lost in the coming years,” he said. “The fragile gains that we’ve achieved will be lost.”

In Africa, many PEPFAR partners and recipients in largely conservative countries don’t support abortion either because of religious beliefs. But the idea that the programme, reliant on the steady supply of HIV drugs, could be subject to political winds is a cause for alarm.

“If PEPFAR goes, who is going to meet that cost?” asked Josephine Kaleebi, who leads an organization in Uganda that helped the programme’s first-ever recipient of HIV treatment medication. “We are proud to say that the first recipient is alive,” Kaleebi said.

The group, Reach Out Mbuya Community Health Initiative, was founded by members of Uganda’s Catholic Church, which is against abortion. In the reception area, portraits of priests line the walls. But Reach Out helps anyone who walks in needing HIV drugs, Kaleebi said. About 6,000 people are served, many of them “the extremely most vulnerable” from one of the poorest areas of Kampala.

Mark Dybul, who helped create and lead PEPFAR under Bush, warned that weakening PEPFAR would also hurt the diplomatic goodwill the U.S. has created in developing regions.

Deaths of infants and young children from AIDS in the region have dropped by 80%. Stopping PEPFAR would be like committing “global genocide”, said Mulongo, the orphanage programme manager. He recalled how helpless he felt watching children die before HIV drugs were readily available. Almost two decades ago, they would lose at least 30 children a month to AIDS.

Elsewhere in Nairobi, 16-year-old Idah Musimbi is part of a generation that has grown up without the fear that an HIV diagnosis was a likely death sentence.

SOURCES: AP News, by Evelyne Musambi, Farnoush Amiri, Cara Anna, Ellen Knickmeyer, 12 September 2023. Associated Press writer Rodney Muhumuza in Kampala, Uganda, also contributed to this report. ; AP News, by Ellen Knickmeyer, 1 August 2023 + PHOTO by Jacquelyn Martin/AP