by Katrina Perehudoff, Lucia Berro Pizzarossa, Jelle Stekelenburg

BMC International Health & Human Rights 2018;18(1):8 DOI: 10.1186/s12914-018-0140-z

Abstract

Background – The World Health Organization (WHO) has a pivotal role to play as the leading international agency promoting good practices in health and human rights. In 2005, mifepristone and misoprostol were added to WHO’s Model List of Essential Medicines for combined use to terminate unwanted pregnancies. However, these drugs were considered ‘complementary’ and qualified for use when in line with national legislation and where ‘culturally acceptable’.

Discussion – This article argues that these qualifications, while perhaps appropriate at the time, must now be removed. First, compelling medical evidence justifies their reclassification as a ‘core’ essential medicine. Second, continuing to subjugate essential medicines for medical abortion to domestic law and cultural practices is incoherent with today’s human rights standards in which universal access to these medicines is an inextricable part of the right to sexual and reproductive health, which should be supported and realised through domestic legislation.

Conclusion – This article shows that removing such limitations will align WHO’s Model List of Essential Medicines with the mounting scientific evidence, human rights standards, and its own more recently developed policy guidance. This measure will send a strong normative message to governments that these medicines should be readily available in a functioning and human-rights-abiding health system.

From the Background section

In 2005, WHO’s then-Director General added a note to the entry on the Model List that read ‘[for use] where permitted under national law and where culturally acceptable’. Such a conditionality risks offering a loophole to governments wary of embracing medical abortion, or abortion in general. Mifepristone and misoprostol’s addition to WHO’s Model List was lauded as an opportunity for medical abortion to reach women in rural and low-resourced settings who may otherwise be unable to seek safe surgical abortion. In 2006, the more specific Interagency List of Essential Medicines for Reproductive Health also included mifepristone and misoprostol with the same adjacent note.

In 2016, the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR), a collection of human rights experts tasked with interpreting these rights, asserted that abortion services are an integral part of the right to health in its ground-breaking interpretation of the right to sexual and reproductive health, General Comment No. 22 (para. 56-57).

Since WHO’s initial move to improve access to mifepristone and misoprostol, mounting evidence of their safety combined with the evolution in human rights law now demand a revised approach. However, the status of mifepristone and misoprostol is unchanged in WHO’s 20th Model List of Essential Medicines published in March 2017. The time has come for WHO to remove the restriction of specialist supervision and to move the combination to the core list of the Model List of Essential Medicines and removing the qualifications.

These moves would send a strong signal to Member States – many of which are signatories to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) and therefore have the responsibility to protect and promote the right to health – to improve coherence between their international commitments and domestic fulfilment of the right. Enhancing policy coherence for sustainable development is a target in Sustainable Development Goal no. 17. These issues warrant thoughtful discussion by WHO’s Expert Committee on Selection and Use of Essential Medicines and support from the broader sexual and reproductive health and rights community.

In the following sections of this paper we first explore the integration of the public health and legal frameworks in light of the CESCR’s recent interpretation of sexual and reproductive health. Thereafter the arguments for two recommendations are presented: 1) mifepristone and misoprostol should be reconsidered as ‘core’ essential medicines rather than ‘complementary’ products; and 2) universal access to these medicines should be in line with human rights law and not unduly restricted by domestic law or cultural practices.

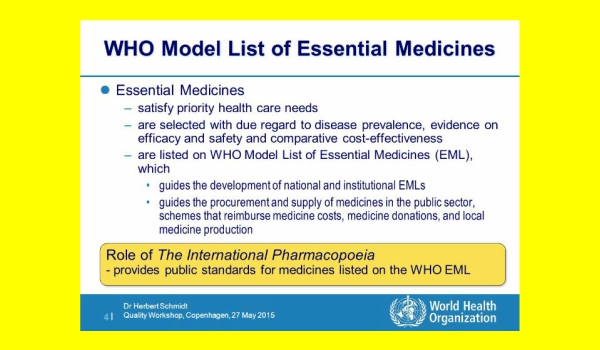

VISUAL, Slideshow by Dr Herbert Schmidt, WHO, 2015, p.4