by Dr Souvik Pyne, Dr Arvinder Nagpal, Dr AlkaBarua

CommonHealth’sBlog, 27 March 2020

“The Medical Termination of Pregnancy (MTP) Act of1971 legally permits abortion services for select conditions thatprovideexemptions from prosecution under the Indian Penal Code of1861.The MTP Act specifies the gestation, facilities, physicalinfrastructure, and service providers for service provision, amended in 2002and 2003 to clarify or define terms used, simplify approval of facilities thatcan provide the services and to keep in pace with medical advances such as theadvent of the medical abortion pills.

“Yet, in India, a woman cannot decide for herselfto have an abortion, rather the Act along with other laws and Actsin thecountry can be and are increasingly used to prevent access to safe abortionservices. In the recent past, the number of cases filed in the court to accesssafe abortion services has increased exponentially. Recent data shows thatmajority (>80%) are conducted outside ‘legally approved or safe’ facilitiesand persons seeking abortion face a range of systemic and legal barriers, inaccessing safe and legal abortion services, especially for gestational periodbeyond legally mandated 20 weeks….”

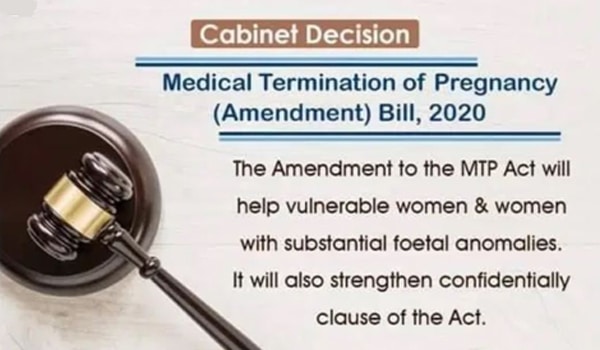

In January 2020, the MTP (Amendment) Bill, 2020 waspassed. This blog summarises the major amendments in the bill and describes themain points made about it during the debate, including on the need for abortionservices; the removal of certain conditionalities (such as removing “married”and replacing “husband” with “partner”; conflation with the Protection ofChildren from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act, 2012 which contradicts and adverselyimpacts service delivery; whether the requirement of medical boards to approveabortions over 20 weeks act is feasible and acts as a barrier; the need toensure that judicial processes do not cause delays; ensuring availability ofservices (till 24 weeks of gestation) in all parts of the country, especiallyrural areas; shortage of trained doctors to provide abortion care, especiallyin urban areas; increasing the provider base to mid-level providers to increasethe provider base; that the right to abortion should belong to the woman; theneed for decriminalisation; mitigating costs and financial burden; specialconsideration for raped tribal women.

While the authors found the debate heartening andsupport for the bill high, they saw the “reluctance of members who are thepolicy influencers to do away with conditionalities that impinge on abortionseeker’s rights and to continue to vest the power of decision-making withdoctors/medical boards/judiciary [as] against the spirit of sexual andreproductive rights enshrined in international human rights and developmentalframeworks”. They make recommendations about doing away with many of theconditionalities, call for “third-party authorisation either through medicalboards or judiciary [to] be done away with”, and for a StandingCommitteeto ensure wider consultations to obtain multiple stakeholders’perspectives.