In a small town in The hills outside Tegucigalpa, there is a stuffed rabbit that knows a little girl’s secrets. “I tell him all my things,” she says. “About how I’m doing, and when I feel sad.” She feels sad a lot lately. “I start thinking about things that I shouldn’t be thinking,” she says. There are a lot of things she shouldn’t be thinking. She was 12 years old and just weeks away from giving birth to a baby when she was interviewed in April this year.

“At first, she said that she did not want to have the baby,” Sofia’s mother said. “She said that she wanted to commit suicide.” When doctors told Sofia she was pregnant and explained that pregnancy meant she was going to have a baby, Sofia, in her soft, small voice, asked whether she could have a doll instead.

When Sofia’s mother found out about the rape, she reported it to the police, and now the man who did it is in jail. But his family kept threatening them, and Sofia and her mom have good reason to worry about what happens once he’s out. Most crimes like this—more than 90 percent—aren’t even prosecuted in Honduras. The few women who do see their attackers go to jail are offered little protection when those sentences end. “If he comes out,” Sofia’s mother says, “I am afraid for my life and her life, too.”

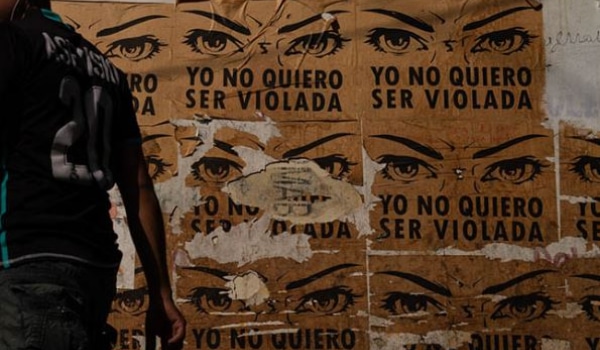

This is just one of the reasons related to violence experienced by women in Honduras for wanting to leave the country. The fraught calculations that face Sofia and her mother are endemic across Honduras, a country that remains in the grip of a rash of violence against women and girls. For some, the answer is simple and disruptive: They have to leave. When exhausted families, mothers toting babies and young women traveling alone arrive at the southern border of the United States, it’s not just gang violence or criminality in general that they’re fleeing. It’s also what Sofia whispers about to her bunny: men who beat, assault, rape and sometimes kill women and girls; law enforcement that does little to curtail them; and laws that deny many women who do survive the chance to retake control and steer their own lives.

As of 2015, Honduras ranked among a tiny group of nations, including war-racked Syria and Afghanistan, with the highest rates of violent deaths of women. Although Honduras’ overall murder rate has decreased in recent years, it remains one of the deadliest countries in the world, and the murder rate has been declining more slowly for female victims. Murder remains the second-leading cause of death for women of childbearing age.

The level of violence in Honduras has gotten attention, but the deeper cultural factors at work are less often plumbed. After two weeks of interviews with more than two dozen women in five Honduran cities and their far outskirts, a portrait emerges of a country where day-to-day violence and misogyny collide with restrictive policies to narrow women’s options to a vanishingly small window of possibility—driving them, sometimes, to flee.

This and other histories of the lives today of women and girls in Central America are the subject of this excellent and heart-breaking article. SOURCE:Politico.com, by Jill Filipovic, 7 June 2019 including PHOTO by Nichole Sobecki/VII