On 29 November 2017, journalism student Paula Umaña published an in-depth feature for the weekly Semanario Universidad as part of Punto y Aparte, a mentoring programme for young journalists. The Tico Times is proud to translate and publish her original piece with Semanario Universidad about therapeutic abortion in Costa Rica. The following excerpts Part I. Two others will follow.

Because of lack of knowledge and fear of legal consequences, health care professionals contribute to the obstacles to therapeutic abortion in Costa Rica.

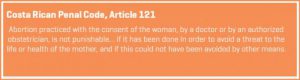

At 24, Lucía is in her last year of medicine at one of the country’s universities. When asked about therapeutic abortion, she says she remembers seeing it mentioned in one class and says “it’s prohibited in Costa Rica”. When she is given information about Article 121 of the Costa Rican Penal Code, which establishes when abortion is permitted, Lucía recalls being told that it’s only done when the woman has a high risk of death due to pregnancy.

Therapeutic abortion is subject to judgments and fears that travel from college classrooms to doctors’ offices. One of the interviewed obstetricians, with more than 25 years in the field, also said abortion is done only when the woman’s life is in danger. The law, she said, does not specify a scope, and therefore “the judicial framework doesn’t allow [abortions] in cases where mental health is affected, or there are fetal malformations incompatible with life.”

When national hospitals were contacted, elusive responses reflected the fact that this topic is still a taboo – reinforced by interviewees who preferred not to be identified by their names for fear of criticism from their peers. For example, to obtain information about the training on therapeutic abortion that medical students at the UCR receive, Medical School Director Lidieth Salazar was contacted. She delegated the response to Dr Flory Morera. However, despite multiple attempts, no answer was obtained.

The number of abortions carried out in Costa Rica’s public hospitals during the past 20 years, registered by the Social Security System (Caja – CCSS), is less than 80, in a country where 70,000 births are attended annually.

The case of Aurora (not her real name) became known internationally some years back. She discovered that her wanted pregnancy would not end well: her fetus suffered from an abdominal wall defect, and his organs were exposed. She continued the pregnancy only because her doctors, who knew the fetus had no possibility of living outside the womb, ordered it, saying that her life was in no danger. They set aside the physical and psychological impact. Her case received a lot of publicity afterwards in local and foreign media, but at the time, she only wanted to end a hopeless pregnancy.

“I can’t understand how the doctor who diagnosed my baby’s disease said that he wasn’t going to suffer. He was drowning in my womb for weeks, with the lungs outside the body, gutted by my organs. Afterwards, I learned that he sucked his own fecal matter until he was born.” she told the newspaper El País in 2013 when she agreed to tell her story. He survived in agony only five minutes.

For Sylvia Mesa, a psychologist at the Women’s Investigation Studies Center (CIEM), “the woman is tortured for no reason. No one takes into consideration what [denial of abortion] implies in terms of psychological and physical suffering in that situation.”

This article includes videos of interviews with Larissa Arroyo, a human rights lawyer and activist who accompanied Aurora to the medical centre to request an abortion, Sylvia Mesa, and two other health professionals.

SOURCE/VISUAL: Tico Times, by Paula Umaña, 25 January 2018