Supreme Court of Brazil: Public Hearing on the Decriminalization of Abortion, August 3rd & 6th 2018– Antecedents, Content, Meanings

by Sonia Corrêa, Sexuality Policy Watch

On August 3rd and 6th 2018, the Supreme Court of Brazil held a Public Hearing on ADPF 442/2017[1], a juridical instrument that challenges the constitutionality of the articles in the 1940 Penal Code that criminalize abortion. This challenge was presented to the Supreme Court in March 2017. In her opening remarks, the then Chief Justice Carmen Lucia defined the hearing as a space opened by the Court for society to manifest its views on the matter and raise arguments that could contribute to a more just judgment.

Background

What conditions favored asking the Court to judge Brazil’s abortion law to be unconstitutional? It is important to address this question because the legitimacy of the Court to address this matter was contested by those who opposed this review. It is also important to clarify why the Court called for public debate on this controversial matter, a process that has provoked surprise and curiosity among international participants and observers of the proceedings.

The decriminalization of abortion via a court decision is rare.[2] The decision in Brazil to contest criminalization through the Court has been described as a response to the obstacles to legislative reform in the last 15 years.[3] Indeed, at the Public Hearing, the representative of Cfemea, a feminist CSO, reminded the Court that since the mid-2000s, federal legislators have abdicated their responsibility to address the detrimental effects of criminalization of abortion on poor, young, and black women, but instead had further restricted abortion.

However, the option of taking the question to the Supreme Court should not be read as a political tactic, aimed at bypassing the legislature. As noted by legal scholar Conrado Hübner: “Parliaments and Courts are recognized today as co-legislators, each with their specificities, with competence to creatively interpret the Constitution”.[4]

Moreover, in the case of Latin American countries such as Argentina, Brazil, Colombia and Mexico, this enlarged role of the high court is a legacy of the broad democratic transformations that have taken place since the 1980s. In Brazil, the Supreme Court (STF) has specifically been legitimized as the guarantor and interpreter of constitutional premises via Article 102 of the 1988 Constitution.

Furthermore, legal initiatives presented to the Court as a legitimate co-legislator gradually expanded after 1999, when Article 102 also defined which public and private entities can legitimately raise interrogations of constitutionality and established that public hearings can also be called to collect the views of knowledgeable, experienced people on the subject being discussed. The Supreme Court has since ruled on the constitutionality of a number of existing laws in a variety of domains. With respect to gender, sexuality and reproduction, the most relevant decisions were those referring to stem cell research (2008), abortion in the case of anencephaly (2012), and same sex civil unions (2011). In the first two of these cases, lively public hearings preceded the judgments.

Although ADPF 442/2017 is therefore not exceptional, never before in the history of the Court have such a large number of Amici Curiae been presented to inform a constitutional review. Hundreds of organizations and people applied to participate in the August 3rd and 6th Public Hearings. Of these, 50 were selected to make presentations, of whom 48 participated. [5]

At the same time, alongside the intensity and visibility of the abortion rights debates in Ireland and Argentina, the Public Hearing and the subject of abortion have gained space in Brazil’s mainstream media. In response, soon after the Public Hearing was announced, anti-abortion forces contested the profile of the participants chosen. Professor Débora Diniz, the coordinator of ANIS, one of the groups who tabled ADPF 442/2017, was viciously attacked, initially through the internet and later on more directly.[6] The atmosphere was therefore both promising and very tense.

In support of ADPF 442: a public health rationale and other relevant lines of argument

On August 3rd, medical doctors, public health professionals, bio-scientists and bio-ethicists, psychologists, legal scholars, social scientists, and feminists expressed their support for and enlarged the arguments presented in the ADPF 442 petition to the Supreme Court, favoring the decriminalization of abortion.

The session started with Dr. Fátima Marinho, speaking on behalf of the Ministry of Health, who presented the most recent epidemiological data on unsafe abortion in Brazil from the 2016 National Research on Abortion, funded by the Health Ministry and coordinated by Débora Diniz, and National Secretary of Health Surveillance (NSHS) estimates for 2008-2017, that between 953,787 and 1,192,234[7] women had had unsafe clandestine abortions. Of them, 210,000 incomplete abortions presented for treatment to the public health system annually, of which some 15,000 were near-miss cases, and in 2016, some 203 women died from unsafe abortion who were predominantly poor, black, young, and with very low levels of education.

Ex-Health Minister Dr. José Temporão, who followed Dr. Marinho expanded our understanding of clandestine abortion as a major public health problem, which cannot be narrowly addressed in moral terms. Then a number of speakers, e.g. Dr. Melânia Amorim, Dr. José Resende (National Academy of Medicine), Professor Rebecca Cook (University of Toronto Law School), and. Françoise Girard (International Women’s Health Coalition, USA) provided solid information on the positive effects of decriminalization on women´s reproductive health.

Four speakers from FEBRASGO (Brazilian Federation of Obstetrics and Gynecology) focused on the detrimental effects of criminalization on health care provision, including fear of providing health care to women with incomplete abortions, post-abortion counseling or contraception. Dr. Thomas Gollop strongly reminded the Court that health personnel who, in the name of the law or moral values, denounce women who have resorted to clandestine abortions and seek care in public hospitals, violate basic premises of professional ethics. Dr. Tania Lago spoke of the ways in which the moral climate surrounding the criminalization of abortion creates obstacles for the establishment of legal abortion services, including to save women’s lives.

At the end of the first day of the Hearing, Dr. Dirceu Grecco (Brazilian Association of Bioethics) recalled how in the 1980s and 1990s, the Brazilian State successfully designed a non-discriminatory and human rights-based response to the HIV and AIDS crisis, a model that should also be adopted to prevent the public health problems deriving from unsafe abortions. He observed that the death of only one woman from abortion-related complications should be viewed as a violation of bioethical standards, because sound knowledge and technology are available to prevent this human loss.

A number of other interventions elaborated on the safety of current abortion methods, particularly with regard to medical abortion pills, by Dr. José Temporão, Dr. Rosires Andrade, Mr. Anand Grover (former UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Health 2007-2014), and Ms. Rebecca Gomperts (Women on Web).

Professor Heloísa Helena Barbosa (IBIOS), recalled previous decisions of the Court in relation to stem cell research and abortion in the case of anencephaly. She emphasized the anachronism of laws that criminalize women when there is no criminal protection of frozen embryos used in assisted reproduction. Mr. Anand Grover said the criminalization of abortion violated the right to health, which is solidly enshrined in the Brazilian Constitution. He reminded the Court that Brazil is a signatory of the International Convention on Social, Economic and Cultural Rights, which supports an expanding understanding of sexual and reproductive health and rights in recent years.

Judge José Henrique Torres pointed out that the unconstitutionality of the Penal Code articles criminalizing abortion is confirmed in international human rights instruments ratified by Brazil. Both he and professor Veronica Undurraga (Human Rights Watch) pointed out that existing criminal laws do not fulfill the objective of protecting the life of the embryo, as millions of women worldwide resort to clandestine abortions every year.

Other key contributions came from feminist activists. Natália Mori (Cfemea) reminded the Court that in recent years an increasing number of women have been subject to criminal justice procedures for illegal abortion. Speaking on behalf of Black feminist organization Crioula, Ms. Fernanda Lopes outlined the flagrant pattern of racial inequality in access to and quality of reproductive health care in Brazil. Noting that the number of black women dying of abortion-related mortality is 2.5 times higher than in white women, she concluded that the criminalization of abortion is a manifestation of institutionalized racism.

In response to anti-abortion voices on the first day of the Hearing, who focused the early stages of life (cells, zygotes, tissues) as the grounding rationale of embryo rights, molecular biologist Professor Helena Nader (Brazilian Society for the Progress of Science) shared this scientific understanding of life: “Even if the notion that life begins at conception is morally acceptable, what science offers regarding the concept of life is neutral evidence about cellular activity, which can neither be evaluated through dogmas nor in isolation, but only through a comprehensive framework based on human rights and constitutional fundaments.”

At the end of the first morning, Professor Débora Diniz pointed out that women who have unsafe abortions are ordinary Brazilian women; they are religious, mothers, black, indigenous, poor, and with low levels of education. She reminded the Court of Ingriane Barbosa, a 30-year-old black woman and mother of three children, who died of a botched abortion in May 2018.[8]

Two other presenters looked critically at the intersection between women’s reproductive autonomy, the right to abortion and the experience and rights of persons with disabilities, a topic that was subject to intense debate when the Zika epidemic hit Brazil in 2015 and re-ignited discussion of abortion rights. Anti-abortion forces attacked those defending the right of women infected by the Zika virus to terminate a pregnancy, describing them as proponents of a eugenic policy that violates the rights of those with a disability. These interventions created strong waves of emotion in the room.

Ms. Adriana Dias, who has glass bones disease and represented the Baresi Institute, a disability rights organization, reminded everyone that ableism is what allows some voices to equate the decriminalization of abortion with eugenic practices. Ms. Dias asserted that women with disabilities struggle hard for sexual and reproductive autonomy and that those who equate abortion and eugenics are cruelly usurping these women’s own voices and life experiences.

The second day

On the second day, feminist analysis and arguments prevailed through pro-choice religious voices and a wealth of legal and juridical reflections developed by four women public defenders and six legal scholars. These women, most of them very young, expanded on the juridical and legal lines of argumentation from the first day. For example, they reiterated the non-absolutist interpretation of the language inscribed in the Inter-American Convention on Human Rights on the right to life from conception.

Ms. Juana Kweitel (Conectas Human Rights and the Instituto Terra, Trabalho e Cidadania), and Ms. Cristina Telles (Fundamental Rights Clinic, State University of Rio de Janeiro) argued that a decision favorable to ADPF 442/2017 would be consistent with international human rights laws ratified by the Brazilian State. Professor Nicácio reaffirmed this consistency through a close examination of Brazilian rules concerning the harmonization of international norms and national legislation, known as rules of conventionality.

Ms. Kweitel later clarified that even though the right to terminate a pregnancy is not explicitly enshrined in human rights instruments from the 1960s and 70s (such as CEDAW), substantive international human rights jurisprudence has been settled in that respect in the last 20 years.

In relation to national civil and criminal law standards and practices, Ms. Ana Carla Matos (Brazilian Civil Rights Institute) reaffirmed the legitimacy of the Supreme Court as a proper place of debate and decision on this matter, contesting the argument by a number of anti-abortion voices that such a decision should be the exclusive prerogative of the Congress. She also clarified that, from a constitutional point of view, it is inappropriate to interpret the right of a not yet born child to inheritance, enshrined in the Brazilian Civil Code, as the absolute right to life from conception.

Defence lawyers Ana Rita Prata and Livia Cásseres shared the findings of recent studies on the profile of women accused of self-inducing abortion who had been subjected to criminal justice procedures in the states of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. These confirmed the class, race and age bias in criminalization, which they condemned as unjust. Ms. Cásseres also commented that health professionals’ associations should take a unified stance against the denunciation of women to the police by health professionals.

Ms. Prata pointed out the failure of the São Paulo Public Defender’s Office to ensure habeas corpus for 30 women condemned for the crime of self-inducing an abortion: in only five cases was the right granted by state courts. She also blamed this on pervasive patriarchal and sexist biases among many in the judiciary.

Ms. Charlene Borges (Federal Defense Office) elaborated on the deep androcentric bias of criminal law and criminal justice procedures. Ms. Fabiana Severo (National Human Rights Council) argued that the articles criminalizing abortion must be read as institutionalized gender-based violence that, expressed through the punitive power of the State, surpasses any test of adequacy or proportionality in terms of the application of penal law. And Ms. Eleonora Nacif (Brazilian Institute of Criminal Sciences) said that the profound gender, race, and class distortions of the law criminalizing abortion allow for the interpretation that women who die from dangerous abortion procedures have been killed by the State.

At the end of an intense second day, Ms. Livia Gil Guimarães (Nucleus of Juridical Human Rights Practices, University of São Paulo) presented a remarkable synthesis of the two days and ended by recalling that the health and life of thousands of women would now be in the hands of the Supreme Court.

Earlier, however, Professor Janaína Paschoal, a criminal law scholar known for her strong opposition to abortion, raised arguments aimed at minimalizing the bleak realities of criminalization.[9] While admitting that that there is constitutional room for the elimination of penalties for self-inducing abortion, she (correctly) alleged that most women condemned for abortion are judicially pardoned and subjected to compulsory community service. But she also suggested that denunciation of women by health personnel should not be blamed because it can be explained by the solitude and stress these professionals experience in emergency wards. These views were later sharply contested, however. Ms. Eleonora Nacif reminded the Court that judicial pardons do not automatically erase the social effects of criminalization, as women remain under the disciplinary gaze of the justice system and are prone to serious stigma and discrimination in their families, schools, religious communities, and the labor market. Lastly, public defender Lívia Cásseres recalled that many of the women denounced by health professionals were subjected to brutal treatment, such as being handcuffed to their hospital beds, and that this treatment cannot be explained away or justified by the conditions of work in the health system.

Who spoke for the opposition?

In contrast to two previous public hearings initiated by the Supreme Court, to discuss the constitutionality of stem cell research and abortion in the case of anencephaly, differences in the anti-abortion camp became clear. They are no longer predominantly Catholic, for example. Amongst the 17 people testifying, four were Evangelical (three male pastors – one of them a senator, and a woman lawyer) and another who represented the Federation of Kardecist Spiritualists. Eight of the 17 were women and there were 12 non-clerical voices, the majority being lawyers and doctors.

Consistent with this secular profile, the often-virulent arguments used were not founded on religious tenets or doctrines. Although God and faith were not entirely absent from their speeches, the main vocabulary they used was biological (cells, zygotes, gametes, genes, genetic imprint, fetal tissues), juridical, legal and statistical, and is being used by all active anti-abortion groups.

For example, Padre José Eduardo de Oliveira e Silva (National Conference of Bishops) stressed the scientific status of his views and complained about those who describe the Catholic Church as fundamentalist fanatics whose aim is to impose their religious vision on the secular state. He insisted that the claim that life begins at conception was strictly a scientific view. Pastor Lourenço Stelio Rega (Brazilian Baptist Convention) declared that he had learned from legal scholar Ronald Dworkin that abortion pertains to the realm of bioscience and genetics, and that his framing of the subject is one that criticizes the “absolutism” of science and instead values a holistic conception of life and the genetic singularity of the embryo. Mr. Luciano Alencar Cunha (Brazilian Kardecist Federation) asked the Court to treat abortion in a manner consistent with laws that protect biodiversity: “If there are legal norms that criminalize the destruction of the eggs of tropical birds and turtles, why can human eggs not be similarly protected?”

The new argumentation against abortion also took on a socio-demographic complexion, as expressed by economist Vivianne Petinelli (a private Institute for Governmental Policies), who underlined the economic potential of the demographic bonus and (erroneously) blamed abortion for the fertility decline in Brazil. Other voices, including priests and pastors, emphasized that abortion must be prevented through poverty alleviation, reproductive health policies, and sexuality education. Last but not least, a large of number of these actors insisted on their own representativeness as spokespersons for large sectors of the Brazilian population and the importance of national sovereignty.

These claims must be contested and questioned, for example, because some of these same actors have systematically attacked gender and sexuality curricula in the public school system. Even so, the overall direction of these views should not to be ridiculed. Rather, it must be read through the critical lens described by Éric Fassin, who pointed out that since the 2000s, the Vatican has begun conflating divine rules, the universalism of natural law, and the laws of nature.[10] Moreover, this bio-juridical and technocratic turn (and the vocabulary that goes with it) is not anymore exclusively Catholic but is now solidly shared across a wide range of Christian groups. No less important is the fact that the language used was, on various occasions, openly political in its allusions to representation and majoritarian opinion. Moreover, the overall tone used by many of these speakers included mentions of tolerance, peace, and agreement (Kardecist Federation), or respect for divergent views, and calls for care and love as the best response to unwanted pregnancies, either to persuade women not to abort, or to find homes for unwanted babies. Yet these calls for tolerance and care were in sharp contradiction to the aggressive tone used in most of the interventions against abortion rights during the whole two days.

Although not everyone who expressed anti-abortion views used an openly offensive tone, as one speaker did, aggressiveness did prevail. The official data on the number of women who have abortions and die of complications of unsafe abortion were contested in quite rude terms, as a political tactic, aimed at disparaging the institutions and individual researchers who did the research – in particular Professor Débora Diniz. Their strategy also aimed to persuade wider audiences that abortion is not the experience of large numbers of ordinary women, but rather a minority issue of “elitist and privileged” feminists. And feminists were indeed one main target of a whole series of belligerent remarks. For example, on the first day, Mr. Hermes Rodrigues Nery (National Prolife and Profamily Association) portrayed feminists as the facile instruments of international powers – such as the Ford Foundation – which are engaged in promoting a cultural mutation, anti-natalist policies, and a “culture of death”. Another described feminists as dogmatic idolaters of desire, who are complicit with sex-selective abortions, capitalist fetal tissue industries, and eugenic policies.

Dr. Rafael Câmara, a gynecologist (Liberal Institute of São Paulo) denigrated all the medical professional associations present at the Hearing. Ms. Angela Gandra Martins (São Paulo Association of Catholic Jurists) described those who defended decriminalization as base, utilitarian, egoistic, and liberal ideologues who had fabricated juridical rules to create rights that do not exist and that would be more properly described as privileges. And so on.

Padre Jose Eduardo (National Conference of Brazilian Bishops) claimed that the Supreme Court was only pretending that different positions were being heard, but what it was really doing was legitimizing what would come next, proven by the fact that those who advocated for abortion as a right had twice the time to speak as those opposed.[11] Pastor Magno Malta (a Senator representing the Congressional anti-abortion caucus) declared that the Court was disrespectful of the principle of division of power between the executive, legislative, and judicial branches – and that the Court was not respected by Brazilian society.

The members of the Supreme Court responded to these attacks firmly and politely. Chief Justice Minister Carmen Lucia called for the Court and the Brazilian people to be respected. because society knows what the role of the Supreme Court is, as defined by the 1988 Constitution, and that the Court would never exceed the role established for it. After Senator Malta’s intervention, Judge Rosa Weber calmly reminded everyone that the petition for decriminalizing abortion reached the Court through a soundly established legal procedure for challenging the constitutionality of existing laws and that the rules for public hearings had been strictly followed, as established by law.

While aggression has long been a tactic of many anti-abortion forces, the hostility that characterized some of the anti-abortion interventions in the Public Hearing must also be understood in relation to the increasing polarization of Brazilian politics since 2013, a situation which has worsened since 2016 and is now being intensified by the presidential election.

The other religious voices: a different tune

It was therefore crucial to hear other voices speaking on behalf of religion, who referred directly to religious texts and the recommendations of religious authorities to express greater flexibility and even to openly support women´s reproductive autonomy in the face of an unwanted pregnancy. These views were expressed by Iman Moshin Ben Moussa (Federation of Muslim Associations of Brazil), Rabbi Michel Schlesinger (Israelite Confederation of Brazil) and in particular by Professor Maria José Rosado Nunes (Catholics for the Right to Decide) and feminist Lutheran Pastor Lusmarina Campos Garcia (Institute for the Study of Religion).

All four of these speakers elaborated the ways in which abortion is accepted in Islam, Judaism, and Christianity, and the changing views of Catholicism until the 19th century were also elaborated. For Pastor Lusmarina, in closing, the power to judge is in the hands of a god who is not focused on punishment but on unconditional love and grace.

To conclude briefly

The two days of Public Hearing were an extremely privileged opportunity to chart the plurality of actors supporting abortion rights in Brazil today and, most particularly, to make visible the breadth and consistency of juridical, social, epidemiological, and scientific arguments and data supporting the decriminalization of abortion. But the Hearing was also a canvas upon which to draw more precisely a cartography of the actors and forces opposing the decriminalization of abortion, as well as the stances informing their positions, the vocabulary they are employing, and, perhaps more importantly, the hostility and aggression of their discourses. Most strikingly, the Public Hearing was a privileged space for the diverse religious views on abortion rights to become more visible in Brazil in ways that strongly evoke the elaboration we developed ten years ago with Rosalind Petchesky and Richard Parker,[12] on the trends, challenges, and pitfalls of contemporary sexual politics, seen with an intersectional lens:

In the present political and geopolitical context – and possibly for the foreseeable future – feminist and sexual rights activists will need to re-engage with religion without “returning” to it. What this means in terms of political analysis and strategy is bringing a critical perspective to bear on religion as a continuous but changing aspect of political and social reality, not its “opposite”. On the one hand, this kind of critical engagement means challenging – loudly and forthrightly – the injustices perpetrated in the name of religion, however and wherever they occur… It can also mean opening doors that a dogmatic or defensive secularism leaves closed – for example, examining the spiritual, ecstatic, and mystical dimensions of sexuality, or forging alliances with religious identified groups where we share common goals and values (p.221).

It is not possible to predict what will come next, in particular because everything concerning Brazilian institutional politics is awaiting the outcome of the general election of a new president and new composition of Congress. But we know abortion is a campaign topic, with anti-abortion slogans being loudly brandished by parliamentarian candidates on the extreme right. But even against this uncertain horizon, it is not excessive to say that the mobilization triggered by the Public Hearing in relation to the updating of data on abortion and the production of arguments and reasoning in favor of abortion rights has been a resounding success. But we must be sharply prepared for the next steps.

FULL TEXT This is a condensed version of the full text of this report in English.

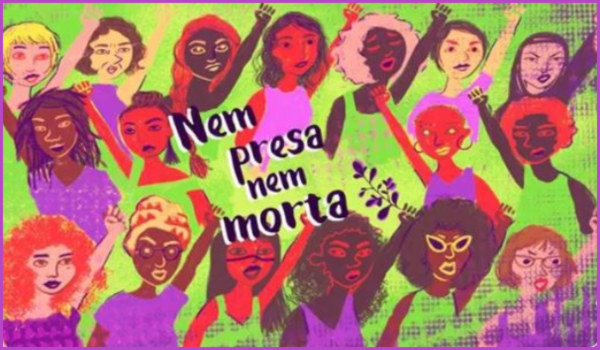

A festival for women’s lives, 7 September 2018, by Angela Freitas, is a short report on activism propelled by the hearing which gathered feminists from across the country over the weekend of the Hearing. Thi report opens: “Feminists, networks and organizations engaged in the struggle for the right to abortion in Brazil had two months to prepare a mobilization and communication strategy around the Supreme Court public hearing on ADPF 442 on August 3 and 6. This way, the campaign #NeitherKilledNorJailed was thought of, to resound on social media in order to widen the abortion debate scope beyond the Court’s walls into society…” VISUAL

Testimony at the Hearing by Professor Rebecca Cook . . .against Unsafe Abortion in the Public Hearing of the Brazilian Supreme Court, Case ADPF 442, Brasilia, August 3, 2018. English original. Em Portugues do Brasil. Español traducido por CLACAI (Consorcio Latinoamericano contra el aborto inseguro). Uno otro en Español.

[1] See http://sxpolitics.org/abortion-rights-at-the-brazilian-supreme-court/16796

[2] The United States (1973), Canada (1988) and Colombia (2006)

[3] See Marta Rodriguez de Assis Machado and Débora Alves Maciel (2017) “The Battle over Abortion Rights in Brazil’s State Arenas (1995-2006)”. In: Paola Bergallo, Alicia Yamin and Marge Berer (eds). Health and Human Rights Journal: Special Issue on Abortion and Human Rights (pp 119-133). Available at: http://sxpolitics.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/HHRJ-19.1-Full-Issue.pdf

[4] Full article in Portuguese: https://epoca.globo.com/conrado-hubner-mendes/ativismo-social-nao-judicial-22983759#ixzz5P36PNNS4

[5] See http://sxpolitics.org/adpf-442-public-hearing-expositors/18869

[6] See https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2018/aug/02/professor-forced-into-hiding-by-death-threats-over-brazil-abortion-hearing?CMP=share_btn_fb

[7] Read in Portuguese

[8] See http://catarinas.info/a-morte-evitavel-de-ingriane-e-lembrada-em-audiencia-publica-sobre-aborto/ (in Portuguese)

[9] Professor Paschoal became internationally known as one the three lawyers who elaborated charges of irresponsible managerial misconduct by President Dilma Roussef, which led to her political impeachment in 2016.

[10] Available at: https://www.religionandgender.org/articles/abstract/10.18352/rg.10157/

[11] The accusation of time imbalance was unfounded, as all speakers were given 20 minutes. As for the numbers of voices speaking against and in favor ADPF 442/ 2017, they were initially proportionate to the number of amicus curiae that had been presented. When this was contested, rapporteur Judge Rosa Weber accepted the inclusion of seven additional participants, of whom three sharply opposed the decriminalization of abortion during the Hearing.

[12] Sexuality, Health and Human Rights, Routledge, New York, London, 2008