by Sophie Cousins

A school physical education textbook in India recently came under fire on social media for defining 36-24-36 as the ‘best body shape for females’, claiming that it was ‘why in Miss World or Miss Universe competitions, such type of shape is also taken into consideration’.

While the textbook wasn’t widely circulated (and local media reports say the government will take action against the publisher of the book as it wasn’t approved for use in schools) it nonetheless highlights a common problem in India: the lack of education on the inner workings of the female body, rather than just its appearance.

The sexual and reproductive health needs of adolescents across India are grossly overlooked by the education system, not understood by the healthcare system and considered so taboo in all areas of society, including among parents and politicians, that they are rarely discussed publicly.

The consequences of a lack of appropriate and adequate sex education along with commonly reported negative healthcare worker attitudes towards teenage sex can have dire consequences and presents myriad barriers to the effective delivery of services to millions of adolescent Indians of reproductive age.

In fact, when a sex education curriculum was promoted by the government in 2007, it was fiercely opposed with many arguing that it was a western construct that would corrupt youth.

The result has been a ban of sex education in numerous states. Other states meanwhile allow private schools to run their own version of sex education with varying degrees of sufficiency while states like Haryana run more liberal education classes in state schools that address sex, contraceptives and “natural urges”.

I recently worked on a piece about India’s small yet declining use of modern contraception and the need for India to educate its youth and move away from its reliance on female sterilisation.

As part of the piece I met a young, vivacious and thought-provoking woman who works in sexual health. She told me she’d never talked about sex or contraception with her mother until her mid-twenties. She’d basically flown blind, she told me.

“In the end, women only access services when they’re pregnant,” she said.

And with this inevitably unwanted pregnancy is included.

While India’s abortion laws are considered liberal compared with elsewhere in the region, a lack of awareness of the laws, a lack of women’s agency, stigma and healthcare worker attitudes are major barriers.

Such barriers can have devastating consequences. In fact, it’s estimated there are more than 6.4 million abortions in India every year, a stark contrast to the official figure of 395,495 recorded between 2015-16.

The wide discrepancy between the estimated number of abortions and the official figure is because government figures only count abortions that are registered by accredited public and private facilities, which is a legal requirement.

But given that two-thirds of abortions in India take place outside accredited healthcare institutions by unregistered healthcare providers or “quacks” or by women who opt for medical abortion tablets which are available over-the-counter, the official figures don’t accurately represent the situation on the ground.

It’s not surprising to learn that complications from unsafe abortion in India are not decreasing, but are actually increasing, according to the executive director of the Population Foundation of India, Poonam Muttreja.

Another barrier is the limits of the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act 1971, which stipulates that getting an abortion on the grounds of contraception failing is only available for married women. What about the rights of unmarried women? And what services are then available for the youth of India who are increasingly becoming more sexual explorative and rejecting early marriage?

While draft amendments to the Act have been tabled which would include allowing an unmarried woman to legally seek an abortion up until 12 weeks,

and another which would allow abortions up to 24 weeks in grounds of serious fetal anomalies, these have yet to be incorporated into the Act and it’s unclear whether or when such changes will be realised.

On this note, I recently met Amrita whose sister, Deepti, got pregnant out of wedlock. She sought an abortion in New Delhi but the doctor refused, asking relentless questions about her boyfriend, her parents and where she lived.

Fearful of being beaten by her family, she had no option but to leave home, marry her boyfriend and continue her pregnancy. In the end, she was jailed for taking part in an illegal marriage and she gave birth in prison.

“Only if I had had the knowledge of contraception and law,” she said at the end of a short film made about her story.

How does one even begin to understand what it would be like to be rejected by your own family because you’d never had the opportunity to understand what contraception is?

I can’t imagine how many young girls like Deepti there must be across India and elsewhere in the region. India’s youth hold the key to the country’s future. But if its youth are going to flourish to their best ability then girls’ and women’s sexual and reproductive health and rights must be realised to their full potential.

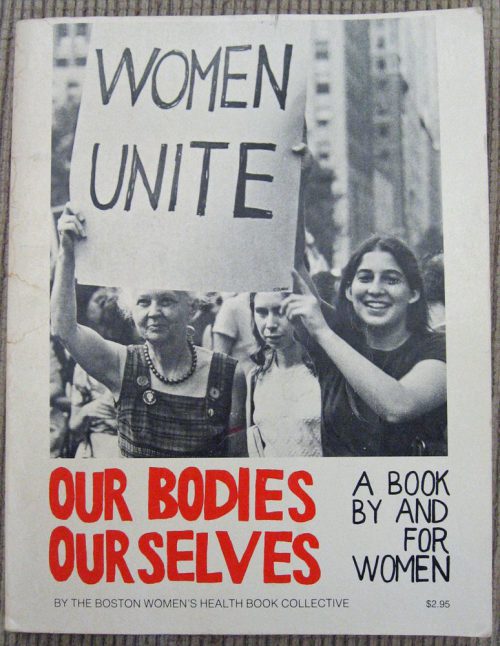

Image: Front cover of Our Bodies Ourselves, published by the Boston Women;s Health Book Collective