Image: Admissions for Complications of Abortion at GPHC, 1991-2025

by Fred Nunes

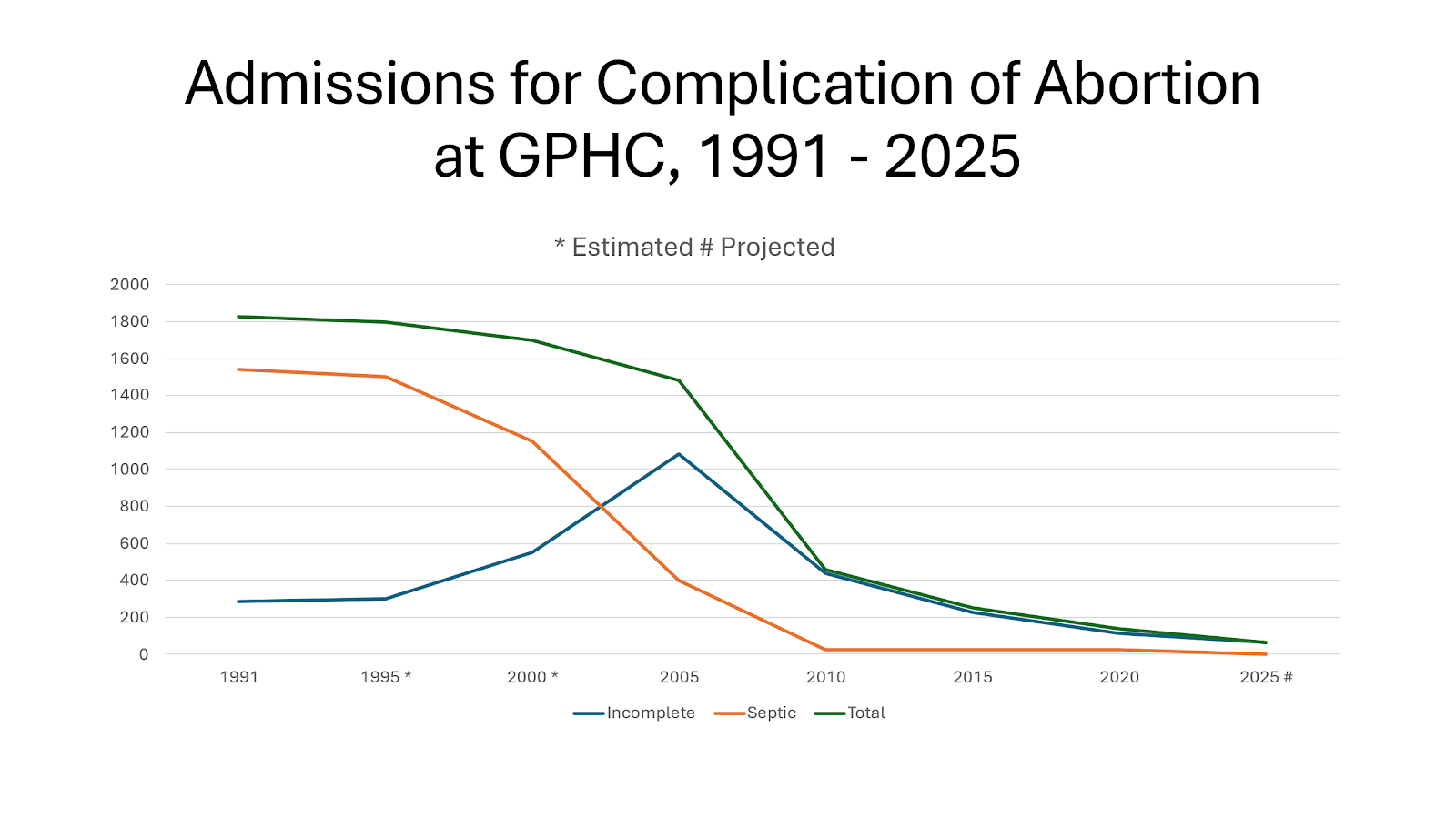

Since the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act 1995 (MTOPA), Georgetown Public Hospital Corporation (GPHC) has experienced a 97% decline in admissions for complications arising from unsafe abortion.

In 1991, there were 1,828 admissions to GPHC for complications resulting from unsafe abortions. These placed septic abortion as the third highest cause of admission and incomplete abortion as the eighth highest cause. Those were the appalling data that triggered my interest in abortion research.

Guyana passed the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act late on 4 May 1995. Based on the first quarter of 2025, the projected admissions figure for complications for the whole year is 61.

The largely religious opposition in Guyana to the law claimed that making abortion legal would result in an increase in abortions, as women would choose abortion over contraceptive methods. Some medical doctors even believed that legalization would overwhelm public hospitals. Both groups were wrong.

Data compiled by the Health Management Information System at GPHC show a dramatic decline in admissions for complications of abortion. We have no data for 1995 and 2000, those are estimates.

The savings are huge. On average it costs about nine times as much to treat complications of unsafe abortion as to provide safe abortion care. In the early 1990s, about a quarter of the blood supply available at GPHC was consumed in treating abortion complications. And an entire ward, Ward E, known as the “Abortion Ward”, was dedicated to that purpose.

In the early 2000s, ASPIRE (Advocates for Safe Parenthood: Improving Reproductive Equity) did a study of the cost of care for complications in major hospitals in Trinidad. We found that the government was spending no less than a million TT$ (US$150,000) per month, treating complications of abortion. We shared our findings with three ministers, two of whom were women. We never heard a word from them. The reluctance of Caribbean politicians to engage in any discussion of abortion is monumental. They shrink.

Legalizing abortion has not only radically improved maternal health, but it has also saved public hospitals millions of dollars. Far from overwhelming hospitals, it has released resources. From being the third and eighth highest causes of admission, complications of abortion are so insignificant that they no longer appear on any listing of causes of hospital admission.

This is the story in the country’s largest urban area. I am now trying to gather comparable data from the regional and district hospitals. I do not expect similar results.

What is interesting is that all of this has happened despite the decidedly passive approach to implementing the law. Almost all senior officers in the Ministry of Health – Ministers, Chief Medical Officers, Permanent Secretaries, Regional Health Officers, Medical Superintendents, Hospital Administrators – adopted a style of timidity and avoidance. With very few exceptions, they did nothing. They exercised no initiative. Such is the social chasm between those who govern and those who suffer.

The day after the MTOP Bill passed in the National Assembly – i.e. several weeks before it became law – two women went to GPHC seeking abortions. They were turned away: “We do not do that here.”

Just imagine the difference it would have made if those women had been welcomed and treated with dignity. The decline in admissions for complications would have been precipitous. We would have been where we are now 15 or 20 years ago. The savings in money and lives would have been even greater.

So why was the leadership in health so cautious, so hesitant, and so reluctant? How do we account for this prolonged period of inertia? It was not until about 2016 that a Chief Medical Officer instructed some public hospitals to start providing abortion services, 21 years after the law had been passed.

An interesting feature of the data on complications is the decline in sepsis. In 1991, septic abortion accounted for 1,542 cases, or 84% of the abortion complications. By 2020, that figure had declined to just 23 cases, or a mere 5% of complications, as most cases were admissions for haemorrhage. There can be little doubt that this swing occurred as women and providers increasingly opted for medication abortion over the older, more intrusive, surgical methods. Access to Cytotec (misoprostol) improved safety.

However, lack of knowledge of the dosage plagued many providers/users – hence the increase in haemorrhage. ASPIRE encountered this problem in the early 2000s. ASPIRE worked with the distinguished Brazilian Ob-Gyn, Aníbal Faúndes, and developed a half-page protocol. One side explained and described the dosage and the other covered side effects. We laminated the information and left it with pharmacists all over Tobago. Within weeks, the problem of haemorrhage disappeared from Scarborough Hospital.

But the protocol we used in Tobago was from a quarter of a century ago. Healthcare professionals should consult WHO’s Clinic practice handbook for quality abortion care (2023), p. 29.

While the decline in the admission for complications at GPHC is impressive, it took far too long, and it was almost certainly largely due to a shift to using medication abortion (MA) pills, which eliminated the risks associated with more intrusive methods and the risk of sepsis. Initially, the huge decline was in septic abortion. But MA has also created a new safe form of access through pharmacists.

In 1995, the MTOPA created space for mid-level providers to offer non-surgical abortions in the first eight weeks of pregnancy. But our doctor-centred culture resisted this provision, and the Ministry of Health refused to implement it. So, we went to the High Court and in 2016 Justice Roxanne George decided unequivocally in our favour. Medex, midwives, nurses, pharmacists, and any suitably trained mid-level healthcare worker could provide non-surgical abortion care in the first eight weeks.

In 2024, our survey of medical opinion showed that almost 30 years after the law had been passed, and nearly 10 years after the High Court’s decision, 77% of health care workers still believed that only doctors could perform legal abortions. The sample size was 518 respondents.

Culture overwhelms law. Belief buries fact.

What is truly amazing is that, even among pharmacists, 94% were unaware that they can lawfully register and provide MA. So, we have a comic situation in which some pharmacists believe they are clandestinely providing MA and are fearful that they are breaking the law!

In addition, the encouraging figures from GPHC are an urban phenomenon. In the hinterland, where population is sparse, distances are huge, transportation is very difficult and time-consuming, the only access to safe abortion must be through mid-level providers. Who speaks for hinterland women? Where are the Toshaos (leaders of indigenous peoples)?

Doctors are still unlikely to take the lead in advancing this aspect of the law. And not one mid-level professional association – not Medex, Midwives, Nurses or Pharmacists – seems to have the appetite to do so. This is a sad absence of leadership. It is inertia.

And yet, without the registration of mid-level providers, the benefits of medication abortion pills for women and girls in the hinterland will remain out of their reach. Thirty years into the law and not a single mid-level health care professional is registered. This major source of provision remains un-utilized. Sadly, we have learned too well how to ignore those who most need our help – the least among us.

Fred Nunes, now retired, lectured at the University of the West Indies and worked with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), and the World Bank (IBRD). He remains committed to supporting women’s reproductive health.

SOURCE: Stabroeknews, by Fred Nunes, 12 May 2025. [The above text is an edited version of this published article.]