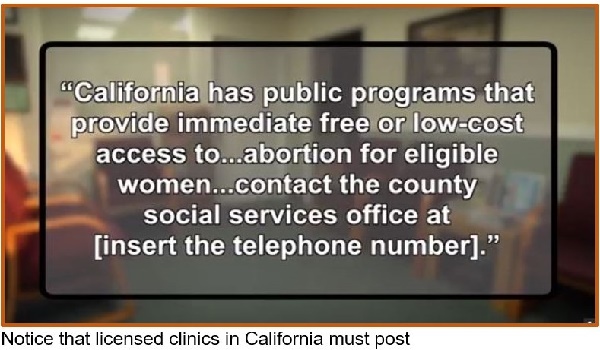

On 20 March, the US Supreme Court heard oral arguments in National Institute of Family and Life Advocates v. Becerra. The case challenges a California law called the Reproductive Freedom Accountability Comprehensive Care and Transparency (FACT) Act, passed in 2015. The Act requires a disclosure by all reproductive health care facilities in the state. Licensed clinics must post a notice that the state provides low-cost contraception and abortion services to those who qualify. Unlicensed facilities must disclose that they are unlicensed.

Just before the law was set to take effect, attorneys from a conservative group sued California on behalf of a group of licensed and unlicensed anti-choice “crisis pregnancy centers”. They argued that the law was not a regulation to protect consumers, but instead an unconstitutional attack on the right of free speech because it forced these clinics to convey a “pro-abortion” message, which they disagree with. A lower court and court of appeals both disagreed and upheld the law. The US Supreme Court agreed to hear the case.

The attorney who spoke first told the justices that California lawmakers had forced the crisis pregnancy centers to “point the way” to abortion clinics in the state and that the law targets them and no one else. He claimed the law appeared to be a neutral regulation but that only crisis centers were exposed to enforcement. Justices Samuel Alito and Anthony Kennedy seemed eager to accept this framing as it reinforces their view that anti-choice activists are being persecuted for wanting to counsel vulnerable patients, rather than a sophisticated network of political and business interests looking to gain as much access to public dollars as possible.

Justice Elena Kagan raised an important critique of this argument when she asked if the California law differed from a Pennsylvania law that the Court upheld in Planned Parenthood v. Casey in which Pennsylvania lawmakers placed a series of mandatory disclosures on abortion providers, including to provide women with information that the state had some financial services available should a patient decide to carry a pregnancy to term. The difference, the anti-choice attorney said, was that the crisis pregnancy centers did not provide medical services.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor then began questioning the attorney. Walking through the landing page of an unnamed CPC website, Sotomayor picked out in great detail all the services provided, including pregnancy tests and ultrasounds. She noted the website said the clients would be seen by nurses and that the centers follow the law on compliance with privacy disclosure requirements. If there are no medical services provided, Sotomayor posited, why would a facility even mention complying with medical privacy laws?

The anti-choice attorney ran out of time before he could fully answer her question, but the question refocused the whole session on the practices these centers frequently engage in. According to a 2010 NARAL Pro-Choice California investigation into clinics in the state, 41% of California counties did not have an abortion provider (which has got worse since), while 91% of counties had at least one crisis center. The study found that 70% of the centers investigated wrongly advised clients that abortion increases the risk of breast cancer, while 60% incorrectly claimed that condoms are ineffective in reducing pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections.

These numbers are staggering, and their implications for patients are devastating. Yet for an hour, even the liberal justices – with the exception of Sotomayor – appeared more concerned with the burden of complying with the California regulations than the harm the law was designed to mitigate.

In McCullen v. Coakley, the 2014 Supreme Court decision that struck down as unconstitutional a Massachusetts buffer zone law, a decision that removed the rights of abortion patients from the picture entirely in support of anti-choice so-called “free speech”. There is concern the California case might go the same way.

US conservatives like these have succeeded in reframing the public debate on access to comprehensive sexual and reproductive health care to focus not on the rights of patients to be free from unnecessary interference in provision of health services, but on the rights of religious objectors to block access to this care. This has also occurred in the attempts to dismantle the birth control benefit in the Affordable Care Act.

The Court will issue its decision in 3–5 months.

SOURCE: Rewire, by Jessica Mason Pieklo, 20 March 2018