The Citizen, a daily newspaper, reported on 10 September 2018 that, on 9 September, Tanzanian President John Magufuli urged Tanzanian women to “give up contraceptive methods” because the country needs more people. “You have cattle. You are big farmers. You can feed your children. Why then resort to birth control? This is my opinion. I see no reason to control births in Tanzania… I have travelled to Europe and elsewhere and have seen the harmful effects of birth control. Some countries are now facing declining population growth. They are short of manpower.” Yet Tanzania has a population of around 60 million people, up from 10 million at independence in 1961.

This news has been reported periodically for some 18 months now, alongside reports that the President has said no pregnant girls are allowed to continue in school during and after their pregnancies. “As long as I am president no pregnant student will be allowed to return to school,” the President said, reacting to a debate in parliament. “We cannot allow this immoral behaviour to permeate our primary and secondary schools. After getting pregnant, you are done.”

One report notes that the President was applauded for remarks like these last year, while others say there has been a wide range of opposition expressed by girls’ rights advocates, both domestically and internationally, including UNICEF.

Last year, Human Rights Watch reported that more than 40% of Tanzanian adolescents are not in school, less than a third of girls have made it to secondary school, and an estimated 8,000 girls drop out each year. Some Tanzanian schools are conducting compulsory pregnancy tests, and expelling girls who test positive, the report said. Once they’d given birth, they were barred from returning. No similar punishment was outlined for boys or the teachers who impregnate their students, although President Magufuli did suggest that men who impregnated schoolgirls should be imprisoned for 30 years and put to work on farms.

One 17-year-old girl told Human Rights Watch: “There are teachers who engage in sexual affairs with students – I know many [girls] it has happened to… If a student refuses, she is punished…”

When Halima Mdee, an opposition member of parliament, attacked the president’s position, the reaction was fierce. The state charged her with insulting the president. “I was telling him he’s not above the law,” she explains. “We have the Constitution, we have laws that provide opportunities here. There are certain conventions and treaties that protect people who are pregnant. Some people might make decisions they regret when they grow up and shouldn’t be punished for them.”

Activists say that it is unfair to hold the vast majority of the girls who become pregnant responsible for their actions. “There are so many cross-cutting issues,” says Valerie Msoka, who works with the Tanzania Ending Child Marriage Network, a coalition of 35 organisations working together to end child marriage in the country. Poverty is a major contributing factor to both child marriage and pregnancy, e.g. girls paying fees with sex, sexual abuse and rape.

There were 69,000 teen pregnancies in Tanzania last year, according to government data. About 21% of girls aged 15-19 have given birth, with the figure rising to 45% in some areas of the country. The child marriage rate is more than 35% nationally, and 59% in Shinyanga. These figures are in fact lower than they were five years ago, but activists fear the President’s stance will reverse the gains that have been made.

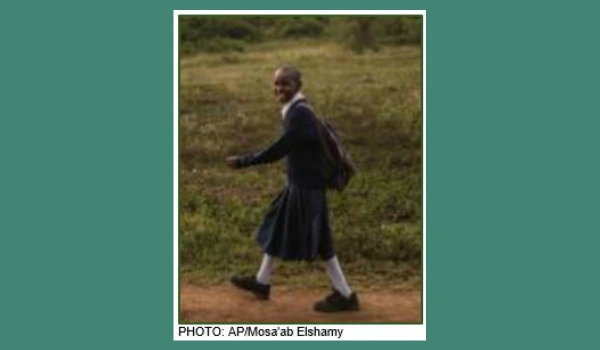

One girl said she was about 15 weeks pregnant when she dropped out of state secondary school in northern Tanzania. “It was difficult to continue because of my appearance… The environment was really uncomfortable. There was no support.” She became pregnant after being raped by her brother-in-law, but her sister called her a liar. She said she was beaten at home, and not provided with food. They were ashamed she was pregnant. She is one of 100 teenage girls studying at the Agape Knowledge Open School in Chibe. All the girls there have been abused, had babies, been rescued from child marriage, or experienced a combination of all three.

Another 17-year-old pupil at the Agape school says she is there because her family is poor. “My relatives forced me to get married for a dowry price of four cows… My mother didn’t support [the decision], but she had no choice. My husband was 31 and I was 12. He forced me to stay at home and I had a baby the following year.” She was rescued shortly after giving birth and her daughter, now three years old, lives with her mother. “I want to go to university to be a lawyer to fight for girls’ rights,” she says with steely determination. “The president should realise we don’t get pregnant by choice,” she says. “I’d like to advise him to think of us and change his mind.”

Last month, in response to continuing protests, the government qualified its position and said pregnant girls would be allowed to pursue vocational training instead of school. And this month they have announced that there is no intention to stop the family planning programme or change the country’s reproductive health objectives. It was explained that the President only wanted to be sure that people did not feel restricted in having children if they were able to feed them, and to ensure the health of women and children.

SOURCES: The Citizen, 15 September 2018 ; Rappler.com, by Agence France Presse, 10 September 2018 ; Financial Times, by John Aglionby, 11 October 2017 ; AllAfrica.com, articles from March 2010 to June 2017 ; Quartz, by Linsey Chutel, 23 June 2017 + AP Photo Mosa’ab Elshamy