A year ago today, Imelda gave birth in the latrine at her family’s small, one-room home with curtains for dividers in a small community. She said she did not know she was about to give birth; instead, she told her lawyer, she “felt something come loose”. She screamed for help, fainted and started to haemorrhage.

Her mother took her to the local public hospital, where they saw that she had given birth. She was pregnant, she told health professionals, because her stepfather had raped her repeatedly from the age of 12. This was documented by the hospital, but not acted upon. Instead, they notified police. At her home, the baby was rescued from the latrine without any injuries.

Imelda was charged with attempted aggravated homicide, although no evidence was presented that she had taken any action to endanger or attempt to murder the baby. She has been in detention for the past year, with a preliminary hearing scheduled for 30 April.

It took until October to get a DNA test to prove Imelda’s stepfather had fathered the baby, even though a judge had approved the request earlier; prosecutors intervened to have the order revoked. The results only reached Imelda’s lawyer in March this year. At that point, a judge issued an arrest warrant, and the stepfather was also placed in detention awaiting trial.

The family’s living situation must have made it practically impossible not to know that abuse was taking place. Imelda’s lawyer Berta María Deleón believes Imelda had difficulty in assimilating the reality of the pregnancy. Imelda told Deleón that when she was giving birth, she still didn’t believe she was pregnant and had no idea what to do. According to Deleón, the stepfather had said that at his age, now 70, he was too old to impregnate her. In addition, she experienced bleeding at times, which she took to be menstruation.

Deleón and Angelica Rivas, a lawyer for the Agrupación Ciudadana por la Despenalización del Aborto, who is working with her, believe that Imelda needs psychological testing and support, given what she has been through, but the prison where she is held have failed to transport her to the clinic where she could be tested. Instead, a limited test was conducted in the prison. They call for her to receive protection rather than criminalisation by the legal system as a victim of both sexual violence and institutional violence by the state.

Under Salvadoran law, the prosecutor has the responsibility to search for evidence that might determine guilt, but also evidence that might determine innocence. Deleón said that in addition to blocking the DNA test and refusing to provide expert psychological exams, the prosecutor has not carried out a thorough study of Imelda’s home environment and social situation, both of which are essential to understanding the family and community dynamics behind the alleged assault and her pregnancy.

“We need to understand why communities normalise the presence of ongoing sexual violence, especially toward girls and adolescents,” Rivas said at a press conference on 5 April.

Deleón explained that what Imelda faces illustrates the intentional institutional barriers that girls and women face when they make rape accusations in El Salvador. According to an extensive study on child sexual abuse in El Salvador published by journalists Maria Luz Nóchez and Laura Aguirre in 2017, the state prosecutor’s office only took up about a quarter of the child sexual abuse accusations it received to court. Of the total rape accusations in 2013–15, only 10% ended with a conviction.

This is a countrywide problem. A study of pregnancies in adolescents and girls by the UN Population Fund in 2016 found that roughly 80% of reported cases of sexual violence against women occurred in girls and women aged 19 or younger. And in about 79% of those cases, the aggressor was a relative or acquaintance of the victim.

Rivas pointed out that the national office of the Prosecutor General of the Republic is working on a project right now to develop improved policies around gender equity. “We congratulate them for their work on developing these policies,” she said at the press conference. “But policies must go beyond documents… shared in a meeting room. They must be translated into the day-to-day work of everyone in the prosecutor’s office and into the everyday lives of women like Imelda.”

Rivas links Imelda’s story with the need to decriminalise abortion in cases of rape, which is currently illegal and the subject of a current bill tabled in the Salvadoran legislature.

Pointing out that women are often arrested after giving birth in latrines, Rivas asked, “Why do women continually need to explain to judges who do not want to listen why they feel the need to defecate when they are about to give birth? There is a scientific, medical explanation that judges and prosecutors should know…Why do judges not understand why so many people in El Salvador have outhouses and latrines rather than porcelain toilets? Why do they not understand the conditions under which people live, instead of judging them for those conditions? Why do they not understand how poverty can impact women and increase the chances of anaemia or pre-eclampsia or other complications during pregnancy…. If a woman arrives and has given birth, but the baby is not present, the assumption is that ‘she killed it’. She is blamed automatically and the system moves quickly to condemn her… but if she says she was the victim of sexual abuse, the system delays for a year, as it did with Imelda.”

“We are not asking for favours. We’re asking them to follow the laws,” she said.

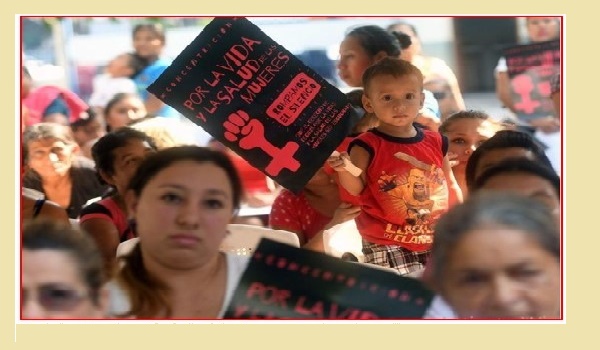

SOURCE: Rewire, by Kathy Bougher, 11 April 2018 ; PHOTO: Marvin Recinos/AFP/Getty Images

TAGS: