Photo: Las Libres “Abortion yes, abortion no, it’s what I decide”

You can also access a brief version of this report here and a pdf version here

by Hannah Pearson

“Confess, you have committed the worst sin in the world” (abortion-news.info, 2016)

When Patricia Mendez, a 21-year-old university student from Veracruz state, miscarried in March 2015, police were called into the hospital ward to watch as she writhed in pain and expelled a dead 20-week fetus. “I was naked, with just the robe they give you, and I had all of them around as I miscarried”, Patricia recounted. “I was in a lot of pain, but nobody did anything. They just said ‘Confess, you have committed the worst sin the world’”. “They treated me worse than an animal. I felt as if I could have died there and nobody would have done anything”, Patricia said of her treatment as she miscarried.[1] Patricia was then made to sign some papers, while a nurse held the fetus to her face and said “Kiss him. You have killed him”. Patricia’s ex-boyfriend’s family held a funeral for the fetus, which they forced her to attend.

Patricia was charged with having an abortion and could potentially be subjected to the “educational measures”[2] stipulated in the Veracruz state law. It is unclear what these measures mean, however, since they are not defined in the legislation and have yet to be imposed or enforced. Her lawyers have managed to stall these charges for the time being, while in the meanwhile, Patricia fled to the central state of Guanajuato to escape social persecution.[3]

Abortion law in Mexico

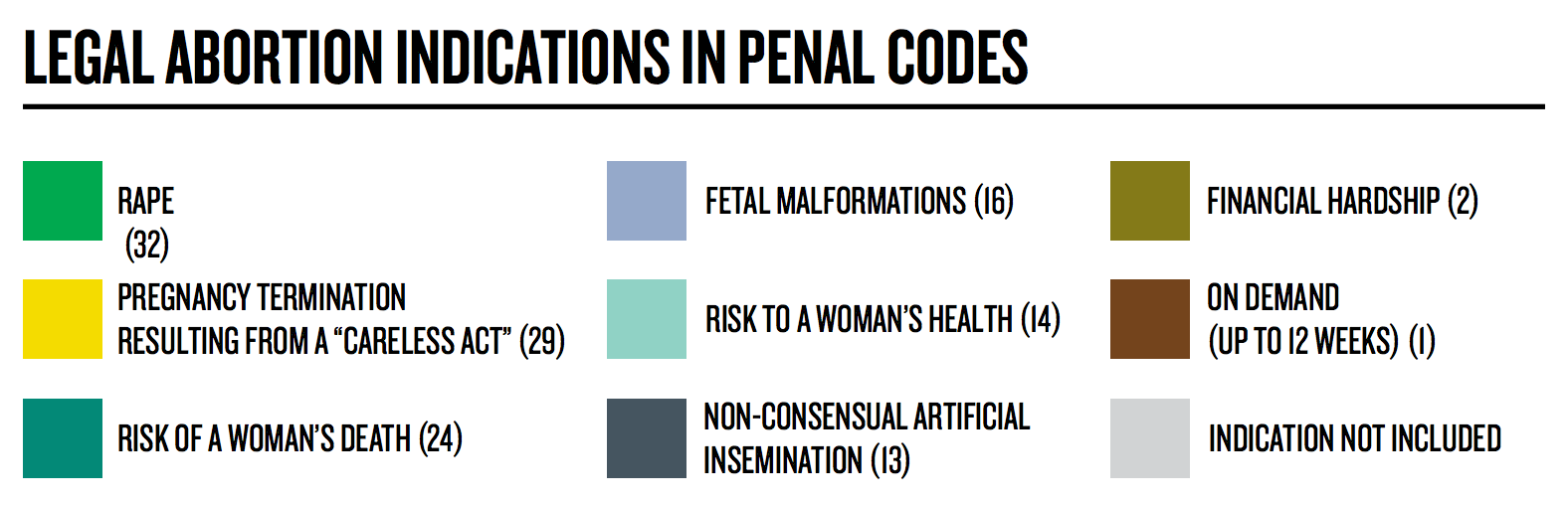

Abortion in Mexico is a crime with exceptions for certain legal grounds. The only legal ground permitted throughout Mexico is if the pregnancy results from rape. Other legal indications in certain states include: serious risk to the woman’s life, fetal malformation, non-consensual artificial insemination, and financial hardship.[4] Legislation varies from state to state; each state’s laws establishes what grounds are legal, what procedure a woman should follow to request an abortion and how/where the service should be provided.[5] The following figure[6] shows in how many of Mexico’s 31 states (plus the Federal District) each of the legal grounds for abortion pertains:

Abortion on request in Mexico City

Mexico City (Distrito Federal) is the only place in the country where abortion has been permitted at the request of the woman during the first trimester of pregnancy since April 2007.[7] This legislation was passed in response to pressure from feminist organisations and many other advocates for women’s health, including health professionals and legal experts.[8] Penalties for abortion after 12 weeks were lowered to a prison sentence of between three and six months or community service of 100 to 300 days.[9] The law included a provision that abortion services must be available to women at the Federal District’s public health facilities, free of charge for residents, and on a sliding fee scale for those living outside Mexico City. In addition, the law strengthened sexual education curricula in schools and called for widespread access to contraceptive methods. Shortly after being passed, the law was challenged in the Mexican Supreme Court by groups opposed to the legislation. In August 2008, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the law.[10]

Elsewhere in the country

Elsewhere in the country, abortion is permitted only under very limited circumstances, and even where it is legally permitted (e.g. in cases of rape or fetal malformation), numerous barriers can make accessing a legal abortion extremely difficult.[11] For example, some states have not amended their criminal codes or health regulations to facilitate access to abortion following rape. In the state of Durango, the requirement that the Public Prosecutor must authorise an abortion following rape is still in the Criminal Code. And in two recent cases that GIRE (Grupo de Información en Reproducción Elegida)[12] accompanied in Durango, the State Secretary of Health required the women to go for psychological evaluation. Yet the Norma Oficial Mexicana 046, which outlines the criteria for care and prevention of sexual and domestic violence against women, revised in March 2016,[13] states that “any woman or girl of 12 years of age who has suffered a sexual assault and has become pregnant has the right to go to any public health centre for an abortion, without the need to submit a complaint of rape and without authorisation from any authority (such as the Office of the Public Prosecutor or a judge) or the consent of a parent or guardian”. It was therefore not necessary for the women to see a psychologist either.[14]

In another case reported in the media in August 2016, a 13-year-old girl who had been sexually abused was refused a legal abortion. Family members took the girl to the police station the day it happened to report the assault and as a result of her complaint and accompanying medical evidence, the public prosecutor charged the man involved. She was not offered emergency contraception at the time. However, when the man’s case went to court, the judge accused him of “illegal sex with a minor” and downgraded the charge by ruling that the man had “gained the girl’s consent by deception”. The state health service also refused to allow the girl an abortion. She was taken to Mexico City for an abortion.[15]

Yet, legal restrictions have not prevented abortion being commonly practised. One study estimated the induced abortion rate in Mexico in 2006 to be 33 abortions per 1,000 women aged 15-44 years, a comparatively high rate by global standards.[16]

Because of legal restrictions, the vast majority of abortions in Mexico take place clandestinely, often in unsafe circumstances, sometimes with severe health consequences for women. From 1990 to 2008, 7.2% of all maternal deaths in Mexico were abortion-related.[17] The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation data reported that the Maternal mortality rate in 2013 was 54 per 100,000.[18] Another study estimated that in 2006, 149,700 women were hospitalized from complications following induced abortions nationally.[19]

The law reform in Mexico City was a response to the gravity of this public health problem, delivering a major victory for women’s reproductive rights. The Federal District’s Government, with the support and encouragement of NGOs, implemented a health service programme for women who sought to terminate their pregnancies, entitled the Legal Abortion Programme (Programa de Aborto Legal). The most recent figures (2015) from this programme show that women from other Mexican states have become users of these services, as well as residents of Mexico City. Especially noteworthy is the case of women from the State of Mexico who represent 24% of total service users, followed by the nearby states of Puebla and Hidalgo.[20] Normative restrictions and a lack of access to abortion in other states compels many women to travel to Mexico City. Nonetheless, and in spite of financial support from groups like Fondo Maria (Maria Fund), who provide financial assistance to individual women, it is not possible for all the women needing safe and legal abortions to come to Mexico City for them.

Data show that the majority of women having abortions are aged 18–24, representing 47.3% of total abortions, followed by 25–29 year olds (22.5%). Between April 2007 and May 2015, the Programme provided services to a total of 141,390 women, making it the principal legal abortion provider in the country.[21] As of April 2016, more than 152,000 public abortion procedures had been carried out in the Federal District.[22]

In fact, the Programme is making such a difference that since 2007, evidence suggests a systematic association between abortion legalisation and reduced fertility in women aged 20-34 years in the Federal District and probably also the greater metropolitan area. That is, by making abortion so accessible and reducing the need to take unwanted pregnancies to term, the law appears to have contributed to lower fertility. The influence is most visible among women aged 20–34, but with limited impact on teenage fertility.[23]

Developments in Guerrero, Michoacán and Tlaxcala

Since 2007, the criminal law on abortion has also been modified in three other states to allow additional legal grounds: Guerrero, Michoacán and Tlaxcala. In May 2014, the Governor of Guerrero, Ángel Aguirre, sent a bill to the state legislature to decriminalise abortion up to the 12th week of pregnancy, the same as in Mexico City. Unfortunately, there were reservations about the bill within the Party for a Democratic Revolution (PRD), including those of Ana Lilia Jiménez Rumbo, president of the Equality and Gender Commission of the Guerrero Legislature, and Lázaro Mazón Alonso, the state Health Minister. The bill was defeated. In November of that year however, the Guerrero Penal Code was amended to include serious risk to the woman’s health as a legal ground for abortion.

Similarly, in Michoacán, a new Penal Code published in December 2014 added new grounds for legal abortion – fetal malformation, non-consensual artificial insemination and financial hardship. The Tlaxcala legislature also reformed its Penal Code to include fetal malformation as a legal indication for abortion.[24]

The anti-choice backlash

Since 2008, in a backlash against the law reform in Mexico City, there were a wave of amendments in certain state constitutions to “protect life from the ‘moment of conception'”.[25] There are now 17 state laws that include this clause, as well as recent bills tabled to include this in two further state constitutions.[26] These were implemented in an attempt to preclude any future attempts to broaden legal indications or decriminalise abortion.

Hence, in spite of the Federal District and some states expanding the legal indications for abortion and the provision of more legal abortion services, the continued penalisation of abortion across most of the country is still leading to women who have abortions being reported and prosecuted.

Criminal sanctions

In both Jalisco and San Luis Potosí, illegal abortion is classified as a felony, meaning that anyone accused of this crime must remain in prison until and during the entire criminal proceedings. In San Luis Potosí, on 29 June 2015, the state legislature approved a reform to Article 407 of the Penal Procedures Code to eliminate this requirement, but the reform is still pending publication. In the remainder of Mexican state penal codes, the crime of illegal abortion is classified as a misdemeanour, which means that women can await criminal proceedings without being imprisoned through the payment of a bond or bail, as established in Article 19 of the Constitution. This payment is, however, a huge burden for many women who are subject to criminal proceedings, as those who are prosecuted are almost always women with scarce economic resources, who could not afford a safe abortion.

Sanctions for the crime of abortion are as follows:

- Prison sentences ranging from 15 days to six years (29 states)

- Fines (13 states)

- Community service (4 states)

- Different types of medical or psychological treatment (6 states).[27]

The Penal Code of Aguascalientes stands out among these as onerous. Its Article 101 establishes two distinct punishments for induced abortion: not only a prison sentence but also a fine for reparations and damages cause to the fetus.[28]

While community service or “treatment” as possible sanctions in place of a prison term could be considered less onerous than imprisonment for the woman, these measures still criminalise women who terminate a pregnancy and treat them as if they have some kind of illness – after subjecting them to criminal proceedings – generating stigma and discrimination that can have serious repercussions for women’s work, and community and family lives. None of these sanctions specifies the type of medical/psychological treatment that is required, who it must be provided by or how long it should last. The laws of Jalisco, Tamaulipas and Yucatán are particularly insidious, as they establish that the aim of such treatment is to “reaffirm the value of motherhood and the strengthening of the family.[29]

Criminalisation

In 2015, GIRE published the most recent available figures on the numbers of women who had been prosecuted for illegal abortion, which they obtained from state judicial agencies. The figures cover the period between August 2012 and December 2013, which included a total of 625 abortions that had been reported to law enforcement agencies throughout Mexico, mainly by hospitals but also by family members, partners and neighbours.

Not all states responded to GIRE’s request for information, so the data do not cover the whole country during those years, nor at this writing were there comprehensive data available for 2014 onwards.

The highest figures came from Mexico City at 183 (for second trimester abortion), Quintana Roo with 81, Baja California with 75, Veracruz with 57 and Guanajuato with 50. Abortion is illegal under most circumstances in Quintana Roo, Baja California and Guanajuato, which explains high levels of reporting in those states. Veracruz criminalised abortion in all circumstances in 2016.[30] It has suffered from some of the greatest governmental and police corruption in Mexico in the last six years,[31] which, coupled with increased anti-abortion activity, could explain the higher rates of reporting there.

However, of the state judicial agencies that did respond to GIRE’s request for information, only Chihuahua, Michoacán and Sinaloa provided information regarding sentences. Information from Sinaloa revealed that where the abortion was allegedly induced with pills, the only material proof which existed was the woman’s confession.[32] The remaining states did not provide any information regarding the outcomes of the reported cases.

Of the 625 cases reported, 75 resulted in criminal prosecution. Some of these were men, presumably either abortion providers, or partners or relatives of the women. Of these, 29 sentences were ultimately handed down for the crime of abortion.[33]

With respect to those persons in custody or in prison for the crime of abortion, state authorities reported 13 individuals in total in custody prior to trial and 9 in prison during the August 2012 to December 2013 period.[34] Information concerning the sex of the individual in jail was not provided in these cases, although GIRE suspects they were predominately women.

GIRE have defended 13 women who were prosecuted for the crime of abortion in 2014-15 alone.[35] In regards to the prosecution of abortion providers, little is known. In 2014, María Leonor Moreno Carreto, a gynaecologist working in the state of Guerrero, told The Guardian newspaper that many doctors in Mexico have found themselves caught between the ethics of patient confidentiality and the law. She said “It’s a question of conscience if a doctor decides to report their patient or not”, and that some doctors have turned their patients in to the police, while others continue to provide abortions regardless of the law, yet continually worry about being caught.[36]

Paola’s story

Paola[37] is from the state of Aguascalientes, and was 20 years old when she fell pregnant. She was in her 25th week of pregnancy when she started to have severe pain in her stomach. She was admitted to the Women’s Hospital of Aguascalientes on 5 March 2014, where she had a miscarriage. In the hospital, the social workers requested the intervention of the Public Prosecutor. A short time later, two investigative policemen arrived to interrogate Paola and her father, who was with her. With uncertainty about her legal situation, Paola requested to be discharged from the hospital that same day.

Paola’s father subsequently hired a private lawyer, thereby finding out that a preliminary investigation had been initiated against his daughter for the alleged crime of inducing an abortion. On 17 June 2014, he was summoned to testify as a witness, without knowing any further details of the case. On the advice of GIRE, he requested a copy of the clinical file. To the best of GIRE’s knowledge, the file did not contain a doctor’s note indicating that Paola had induced an abortion. Under these circumstances, GIRE filed a motion to intervene as Paola’s legal representative, which to date has not been answered, and access to her case file continues to be denied.

In September, the police went to Paola’s home with what they said was an arrest warrant, although this was never shown to Paola herself. GIRE filed an amparo (a federal lawsuit challenging the official acts of a federal, state or municipal authority for consideration of whether it is unconstitutional) to ascertain the reason for her arrest. No information was obtained. However, the Public Prosecutor cancelled the warrant, the amparo was suspended, and Paola was released from custody. Although this was of course good news, the case has not actually been resolved despite GIRE’s intervention, and Paola continues to live with uncertainty and in fear of prosecution.[38]

Martha’s story

Martha is from the state of Veracruz. In early 2015, when she was 21 years old, Martha went to see a doctor complaining of uncomfortable stomach pains. The doctor diagnosed gastritis, and gave her treatment for this condition. In March 2015, Martha began experiencing severe stomach pains, so she returned to the doctor, where she had a miscarriage. Rather than recognise their own negligence for not identifying that Martha was pregnant, Martha’s doctor reported her to the police, who charged her with the crime of abortion. Las Libres have also taken on Martha’s case, which is currently waiting to be heard in court.[39]

Prosecutions for the crime of homicide or infanticide

The manner in which amendments to state constitutions have established the protection of the embryo/fetus in certain states has awarded “legal personality to the embryo,[40] which is extremely threatening in terms of the criminalisation of women who induce abortions, as well as women who experience miscarriages and stillbirths. Some women have been accused of the crime of “homicide of a family member” or “infanticide”, not the crime of abortion, for which the punishment is notably less.

Between August 2012 and December 2013, GIRE learned of 10 cases relating to the crime of “homicide of a family member” or “infanticide” that were reported to law enforcement agencies in different parts of Mexico. Six of the 10 cases resulted in criminal prosecution and of those, three women were sentenced.

And the work of the Centro Las Libres[41] made international headlines in 2016 when 7 Guanajuato women who had been accused of inducing abortions and jailed on homicide charges were set free, thanks to their successful legal defence.[42]

Prosecutions not based on bona fide evidence

In two cases taken up by GIRE in 2013, claims to have evidence of misoprostol use to prosecute the women was said to come from a blood test in one case and a urine test in the other. These claims led Gynuity Health Projects to analyse whether they were scientifically bona fide. GIRE was able to challenge the evidence in both cases.[43] The two cases were as follows: Angela, a 29-year-old indigenous woman of Otomi descent, was living in extreme poverty in the State of Mexico. She was raped several times by her ex-partner. One day, while carrying corn to the mill at work, she began to have severe abdominal pains. When she began to haemorrhage, she went to the hospital for help, where she was accused of allegedly inducing an illegal abortion. She was arrested and transferred to the Public Prosecutor’s Office, where she was detained for 48 hours. A pre-trial investigation was initiated against her for an illegal abortion allegedly carried out using misoprostol pills. The health personnel claimed they found misoprostol in a urine sample.

In the other case, In Baja California (a state that “protects life from conception”) Carla, 32 years old, was taken to a public hospital for care after haemorrhaging in the bathroom of the supermarket where she worked. Based on an anonymous report, the state Public Prosecutor initiated a pre-trial investigation against her for an illegal abortion, allegedly carried out with misoprostol pills. Carla was arrested and held in custody while she was still recovering in the hospital. The health personnel took a blood sample where they allegedly found misoprostol. Carla had to pay bail in order to avoid being sent to prison. She never made any statements regarding having used pills nor was there any evidence to that effect. After receiving support from GIRE, the Public Prosecutors concerned had to set both women free due to lack of actual evidence. (Personal communication of Regina Tames of GIRE to Marge Berer, 16 January 2014).

GIRE also asked state authorities about the use of the “lung float” or hydrostatic test[44] as proof of the crime of killing the fetus/neonate, a test that has been widely discredited in the scientific community. Twenty-one states confirmed that they apply this procedure and passed sentence on the basis of it.[45]

Adriana’s story

On 22 January 2014, Adriana,[46] an indigenous woman from the state of Guerrero, was released from the Chilpancingo prison after seven years and nine months of incarceration, having been imprisoned for “homicide of a family member”. Adriana had had an abortion was she was 18, and her family had reported her to the police. She was sentenced to 27 years in prison. Adriana did not speak Spanish at the time of her trial and did not have access to an interpreter or effective legal defence. Her sentence was later reduced to 22 years after an appeal filed by Las Libres. The Supreme Court, which took 2.5 years to hear Adriana’s case, finally granted her amparo and her immediate release was ordered.[47]

Discussion

The prosecution and imprisonment of women for the crime of abortion, and in some cases for the crime of “homicide of a family member” or “infanticide”, continues to be a reality in Mexico. Local legislatures have continued to table bills to protect “life” from conception, with the intent of criminalising women for illegal abortions and curtailing their reproductive rights. Until and unless there is federal constitutional reform, legal support for women at the state level as cases arise will continue.

In 2016, the Mexican Supreme Court debated the decriminalisation of abortion at the federal level for the first time. The case arose from an injunction filed by a woman who was denied an abortion on legal grounds in 2013. It was symbolic in that she was able to have an abortion in a private clinic, but a favourable ruling would have set an important precedent. Presented by Supreme Court Justice Arturo Zaldívar, it proposed that current sanctions on abortion, as prescribed by the federal Penal Code, violated women’s rights to personal development, sexual and reproductive health, and freedom from discrimination. “An abortion is a drama for any woman. To criminalize them is not a solution that can be upheld from a constitutional point of view,” said Zaldívar. “To condemn [women] to jail, to clandestinity, to put their health at risk, implies a neglect of their value as a person, whose wishes and interests are relevant and significant when considering the harsh decision to terminate a pregnancy.” In 2016, the Court voted down Justice Zaldívar’s proposals three to one, but stated that new proposals revisiting the abortion issue could be considered in the future.[48]

Mexico City’s abortion legislation has been an important first step to improve women’s reproductive health and rights in Mexico, and to legitimise abortion as a women’s health and rights issue, but the continued restrictive abortion legislation in all the states of Mexico, and the conservative backlash, has resulted in continuing unsafe abortions in all of Mexican states and continued prosecution of women who seek abortions. To end unsafe abortions and ensure equal access to reproductive rights and health for all Mexican women, abortion legislation needs to be reformed across the entire country.

“Women should be the compass that guides the law on this matter, because the law ultimately affects them and their lives.” (Centro Las Libres) [49]

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to GIRE (Grupo de Información en Reproducción Elegida) in Mexico City and Centro Las Libres in Guanajuato, for sharing their information and expertise. Reviewed by Verónica Cruz Sánchez from Las Libres. Edited by Marge Berer.

[1] Mexico Supreme Court receives case on abortion re-education program. 7 September 2016. http://abortion-news.info/mexico-supreme-court-receives-case-on-abortion-re-education-program/.

[2] GIRE (Grupo de Información en Reproducción Elegida), 2017. Causales de Aborto en Códigos Penales Estatales. https://gire.org.mx/consultations/causales-de-aborto-en-codigos-penales-estatales/.

[3] Sarah Faithful, 2016. Mexico’s choice: abortion laws and their effects throughout Latin America. 28 September 2016. Council on Hemispheric Affairs. http://www.coha.org/mexicos-choice-abortion-laws-and-their-effects-throughout-latin-america/.

[4] GIRE, 2015. Women and Girls Without Justice: Reproductive Rights in Mexico. http://informe2015.gire.org.mx/en/#/Home.

[5] GIRE, 2017. Op cit ref 2.

[6] GIRE, 2015. Op cit ref 4 p. 62-63

[7] Official Gazette of the Federal District, 2007. ‘Decree reforming the Federal District Penal Code and amending the Federal District Health Law’ [in Spanish] (70): 2-3.

[8] Edith Y. Gutiérrez Vázquez and Emilio A. Parrado, 2016. ‘Abortion Legalization and Childbearing in Mexico’. Studies in Family Planning 47(2): 113-131.

[9] Jennifer Paine, Regina Tamés Noriega and Alma Luz Beltrán y Puga, 2014. ‘Using litigation to defend women prosecuted for abortion in Mexico: challenging state laws and the implications of recent court judgements’. Reproductive Health Matters 22 (44): 61-69.

[10] Madrazo, A, 2009. ‘The evolution of Mexico City’s abortion laws: from public morality to women’s autonomy’. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics 106 (3): 266-269.

[11] Human Rights Watch, 2006. ‘The Second Assault: Obstructing Access to Legal Abortion After Rape in Mexico Report, 18 No. 1(B). http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/mexico0306webwcover.pdf.

[12] GIRE is a Mexican NGO whose mission is to promote and defend women’s reproductive rights within the context of human rights. See www.gire.org.mx.

[13] See http://www.animalpolitico.com/blogueros-punto-gire/2016/04/18/aborto-por-violacion-y-nom-046-un-antes-y-un-despues/ for further details (in Spanish).

[14] GIRE. Durango dificulta acceso al aborto en casos de violación sexual. 9 March 2017. https://gire.org.mx/durango-dificulta-acceso-al-aborto-en-casos-de-violacion-sexual/.

[15] Teenage rape victim denied abortion in Mexico after judge rules attack was ‘consent by deception’. 5 August 2016. http://www.safeabortionwomensright.org/teenage-rape-victim-denied-abortion-in-mexico-after-judge-rules-attack-was-consent-by-deception/.

[16] Fatima Juárez, Susheela Singh, Sandra G. García and Claudia Diaz Olavarrieta, 2008. ‘Estimates of induced abortion in Mexico: what’s changed between 1990 and 2006?’. International Family Planning Perspectives 34(4):158-168.

[17] Schiavon R, Troncoso E, Polo G, 2012. Analysis of maternal and abortion-related mortality in Mexico over the last two decades, 1990-2008. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics 118 (2): 78-86.

[18] Kassebaum NJ, Bertozzi-Villa A, Coggeshall MS, Shackelford KA, Steiner C, Heuton KR, et al. Global, regional, and national levels and causes of maternal mortality during 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2014;384(9947):980–1004. http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(14)60696-6/abstract

[19] Juárez, et al, 2008. Op cit ref 12.

[20] GIRE 2015: 86. Op cit ref 4.

[21] GIRE 2015: 87. Op cit ref 4.

[22] Data from GIRE, April 2016, in http://www.safeabortionwomensright.org/las-libres-guanajuato-a-feminist-approach-to-abortion-within-and-around-the-law/. (Original source no longer online)

[23] Edith Y. Gutiérrez Vázquez and Emilio A. Parrado, 2016. ‘Abortion Legalization and Childbearing in Mexico’. Studies in Family Planning 47(2):113-131.

[24] GIRE 2015: 64. Op cit ref 4.

[25] GIRE 2015: 94. Op cit ref 4.

[26] GIRE 2015: 95. Op cit ref 4.

[27] GIRE 2015: 100-101. Op cit ref 4.

[28] GIRE 2015: 102. Op cit. ref 4.

[29] GIRE 2015: 102. Op cit. ref 4.

[30] International Campaign for Women’s Right to Safe Abortion, 2016. ‘Abortion banned by governor of Mexican state Veracruz’. http://www.safeabortionwomensright.org/abortion-banned-by-governor-of-mexican-state-veracruz/.

[31] David Agren. Abortion banned by controversial Mexican state governor. The Guardian. 29 July 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/jul/29/abortion-banned-controversial-mexican-state-governor-veracruz.

[32] Agren Ibid.

[33] GIRE 2015: 104. Op cit. ref 4.

[34] GIRE Ibid.

[35] Personal communication with GIRE, 28 November 2016.

[36] Allyn Gaestel, Allison Shelley. Mexican women pay high price for country’s rigid abortion laws. The Guardian. 1 October 2014. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2014/oct/01/mexican-women-high-price-abortion-laws.

[37] Name was changed to protect privacy.

[38] GIRE 2015: 107. Op cit. ref 4.

[39] Centro Las Libres, 2017. Articulo Javier (Caso Martha Patricia).

[40] Paine, Tamés Noriega and Beltrán y Puga 2014: 63. Op cit ref 9.

[41] Centro Las Libres is a feminist organisation whose primary mission is to promote and defend women’s human rights in the state of Guanajuato and across Mexico. See http://www.laslibres.org.mx/.

[42] Las Libres, Guanajuato: A feminist approach to abortion within and around the law. 28 April 2016. http://www.safeabortionwomensright.org/las-libres-guanajuato-a-feminist-approach-to-abortion-within-and-around-the-law/.

[43] Gynuity Health Projects. Claims of Detection of Misoprostol in Women Accused of Induced Abortion. 2013. http://files.ctctcdn.com/2ebd04b4201/f1ecfcf9-99ea-4ab6-b4d0-9e9cee65a527.pdf.

[44] The hydrostatic test is a test to determine if a fetus was born alive based on whether or not the lungs float when placed in a recipient of water. This test has been discredited since multiple factors exist that could allow the lung to float without the fetus having breathed after birth. GIRE 2015: 111. Op cit. ref 4.

[45] GIRE 2015: 111. Op cit ref. 4.

[46] Name was changed to protect privacy.

[47] GIRE 2015: 112. Op cit ref. 4.

[48] Mexican Supreme Court of Justice rejects proposal to decriminalise abortions 3-1. 6 July 2016. http://www.safeabortionwomensright.org/mexican-supreme-court-of-justice-rejects-proposal-to-decriminalise-some-abortions-3-1/.

[49] Centro Las Libres, 2017. ‘Articulo Javier (Caso Martha Patricia)’.