The headline in the Washington Post on 7 February was: “The panic is over at Zika’s epicenter. But for many, the struggle has just begun.” The article opens: “In this city at the heart of the Zika outbreak, the gloom and dread have lifted from maternity hospitals and delivery rooms. The scary government posters with giant mosquitoes have mostly come down. Fertility clinics are busy again. At one public hospital that has delivered 1,700 newborns over the past five months, doctors haven’t seen a single case of Zika-related birth defects. ‘It’s as if we’ve all forgotten about Zika,” said [one woman], 17 weeks pregnant, who had waited for the epidemic to pass before she and her husband tried for their second child.'”

This is an optimistic remark but the fact is, cases have not disappeared, even though the numbers have fallen, and families are coping with the children who were born, as the article reports with many examples.

As many as 70% of Recife’s inhabitants contracted Zika in 2015 and 2016, according to Pedro Pires, an obstetrician-gynaecologist who specializes in Zika. However, that high rate of infection likely prevented a revival of the epidemic in recent months because most of the population has become immune. It’s now a year since a global health emergency was declared. By mid-2016, the number of reported cases of microcephaly in Brazil had fallen to about 100 per week, compared to the highest reported number of 640 cases in mid-November 2015. But it is still around 100 a week.

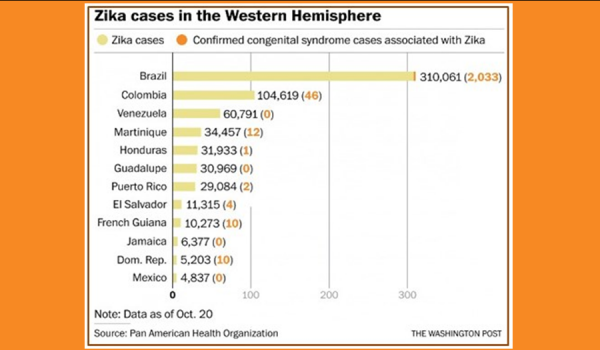

Public spraying of mosquitoes was being carried out widely. Genetic research to make the carrier mosquito unable to multiply was started and research on an anti-virus was also begun. Then it became clear over the course of 2016 that 75% of the cases of seriously affected newborns reported by October 2016 were mainly restricted to the northeast region of Brazil. Moreover, of the 2,600 microcephaly cases reported across the Americas as of 26 January 2017, 2,400 were in Brazil.

Meanwhile, in 2016, the birth rate among the more affluent population of the state dropped by as much as 45%, while state-wide it fell by 7%. Other causes of the syndrome in infants, that may have interacted with Zika, are still being sought.

SOURCE: Washington Post, by Marina Lopes, Nick Miroff , 7 February 2017 ;

INFOGRAPHIC: PAHO in Washington Post, 25 October 2016